In order for a sentence to be grammatical, を must append to a noun.

In your sentence though, we want that noun to be an action (verb), so that’s what の (and sometimes こと) are used for. There are two ways to interpret your sentence:

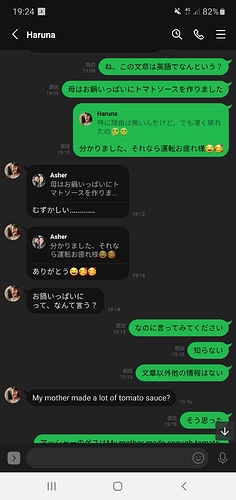

[彼]が [外国に行くの]を [見送りました]。

“He saw (someone) off to another country.”

(Here, 彼 is interpreted as the doer of 見送る)

Or,

[彼が外国に行くの]を [見送りました]。

“(I) saw him off to another country.”

(Doer of 見送る left unstated)

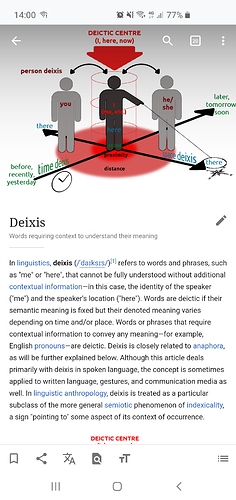

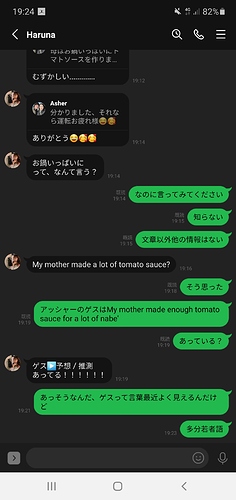

A speaker leaving themself implied as the actor of a (sentence-final) action in Japanese is extremely common. Conversely, a speaker implying an unstated 3rd party mid-sentence is… well, I don’t want to say it never happens, but without any additional context (since we obviously have none to work with here), the one implying “I” is a much “safer” (more likely-to-be-accurate) default interpretation.

Semi-related tangent:

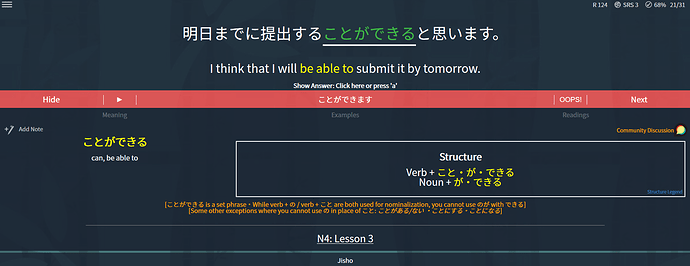

As I understand it, the difference between using こと and の as a verb nominalizer is that [verb]こと ~= “the concept of [verb],” and [verb]の ~= “the action/execution of [verb].”

A lot of times こと and の are interchangeable, but not always. While I’m not sure whether こと is actually wrong/unnatural in your sentence, の still stands out as the go-to choice here since it’s referring to a specific instance (the action/execution) of something that is being 見送る’ed