Thank you for detailed explanation! I suspected as much, but it’s good to hear proper explanation with examples! I guess I should just get used to this usage of ~たら as well

In the wild I hear たら used as ‘when’ farrr more than とき、とき actually seems to be used about large time frames 高校生の時 for example, where たら is almost always used for small time frames/moments. 仕事が終わったら連絡してね (contact me when you finish work).

I guess upon closer thought, たら、is used to highlight transitions in time (when you start something, finish something, notice something) etc.

Actually, upon even closer thought I am half inclined to suggest changing たら、It has always been taught as when/if, but really, it is actually much… much simpler. How about changing the explanation of たら to ‘from when/just when’. Because たら always has this meaning… Always. And we use ‘from when/just when’ quite often in English. What that means to say is, the ‘when’ here is always highlighting new information or a condition that comes afterward.

That would teach people immediately that it is a future/hypothetical ‘when’, rather than giving people the false sense that they can use it for describing time periods, rather than consequences of actions/states.

Just checked with a few natives to see if this is right, it is. The only time it means if is ‘when and if’, which is the same as ‘just when’

For example

高校生の時楽しかった “When I was a high school student I had so much fun”

高校生だったら、楽しかった -looks weird right? actually it’s still correct, there is just info missing. Maybe I am old now and no longer capable of the same things I was when I was a high school student. I try to to climb Mt Fuji then say 高校生だったら、楽しかった. “Gosh, just when I was a highschool student this was fun… now it’s too hard”(unsaid).

I came to a very similar conclusion, actually!

I’ve noticed that I’ve defaulted to always thinking of ~たら simply as “when,” bearing in mind that it can also indicate supposition if there’s any uncertainty present in the context (which is often, but it’s easy to identify). It feels as easy as the conditional と to me now (which always implies an automatic/guaranteed consequence, and can’t append to past-tense verbs).

In comparison to those, the 使い分け between ~ば and (の)なら is still slightly fuzzy to me. I used to think that they were the exact same (because なら apparently originally came from ならば), but now I’m not so sure

I can “feel” a difference between them, but I’m not confident enough to try to explain it here

I concur too. I can’t come up with any example that たら couldn’t be when. I’d say it is also mostly used as when and not as if-when, when I see it. (見たら。。。 )

)

I forgot to mention, as for the difference in なら and ば、It comes back to the ‘true’ passive of Japanese, which is much easier than what textbooks teach. because ば requires the れ change to the verb, all it is doing is changing the perspective of the ‘if’ so that it seems passive.

If I go to work early, I can finish writing my document for sure.

早く仕事に行くなら、資料を書き終わるはずです。

If work gets gone to early, I can finish writing my document for sure.

早く仕事に行けば、資料を書き終わるはずです。

In English the second one sounds almost a little silly, but in Japanese it is a way of making something just a touch more polite. All the え family of verbs do is take away ownership of actions. Hence why verbs like 見える get seen、聞こえる get heard、教える get taught, are all much simpler if we make the English ‘more primitive’

僕にこれを教えて? literally means ‘can you get me taught this?’

ここから富士山が見えるの? ‘Can fuji get seen from here?’

This rule holds true for almost all verbs (any verb that uses kana). Thats why knowing the sound rules of Japanese makes using the particles so much easier. The target becomes clear.

I guess this is why 得る (える)literally means to get. But it holds true for all the え、け、せ、て、ね、へ、め、れ、sounds in verbs (so long as it is かな)If the sound is part of a kanji, it doesn’t count.

@Asher @Kai thank you very much guys! After such a detailed discussion there it is clear as day

And I agree now that it might be a good idea to consider different translation for the grammar point here.

Now, if you don’t mind I would like to continue with the topic as I originally proposed and ask another question.

This:

彼が外国に行くのを見送りました。

I saw him off on his trip overseas.

I have a bit of hard time trying to parse the ~行くのを part. The meaning as a whole is clear, but I can’t quite understand what role does this construction serve in the sentence.

In order for a sentence to be grammatical, を must append to a noun.

In your sentence though, we want that noun to be an action (verb), so that’s what の (and sometimes こと) are used for. There are two ways to interpret your sentence:

[彼]が [外国に行くの]を [見送りました]。

“He saw (someone) off to another country.”

(Here, 彼 is interpreted as the doer of 見送る)

Or,

[彼が外国に行くの]を [見送りました]。

“(I) saw him off to another country.”

(Doer of 見送る left unstated)

A speaker leaving themself implied as the actor of a (sentence-final) action in Japanese is extremely common. Conversely, a speaker implying an unstated 3rd party mid-sentence is… well, I don’t want to say it never happens, but without any additional context (since we obviously have none to work with here), the one implying “I” is a much “safer” (more likely-to-be-accurate) default interpretation.

Semi-related tangent:

As I understand it, the difference between using こと and の as a verb nominalizer is that [verb]こと ~= “the concept of [verb],” and [verb]の ~= “the action/execution of [verb].”

A lot of times こと and の are interchangeable, but not always. While I’m not sure whether こと is actually wrong/unnatural in your sentence, の still stands out as the go-to choice here since it’s referring to a specific instance (the action/execution) of something that is being 見送る’ed

I was going to write this myself and then saw you appended it at the end. Yep… that’s basically the crux of it. If you can ‘do’ something, (in a way that someone else can see), then の is usually better. こと is conceptual. I like to think of it like this, if somebody can see what you are doing, but not ‘know’ without asking you, こと is better. Hence why feelings etc can be either depending on how obvious they are.

I like more literal translations for stuff like this.

‘His going overseas/his departure overseas, is what I saw him off on’

keep in mind that the の here still gives ownership to that action. We do this in English all the time… but not with these types of verbs. for example

‘I went to see his graduation’. Apart from the order of the words this is the same.

彼が卒業するのを見に行った

I try to usually think of の after verbs as simply giving that verb ownership, like in those examples. As for the が、は implies the constant state of something, が implies a temporary or unusual event. Hence why It makes more sense that you are ‘は’ here. You saw him off, but then continued your day to day life.

He is が because you are telling this story from your perspective, and this event was only temporary, in which he (が)was the unusual event.

I think i am missing an important grammar point here.

食事しょくじ のあとで、お皿さらを洗あらわなくてはいけない

I read this as i dont have to wash the dishes after a meal, but it is translated as: I have to wash dishes after a meal. what am i not seeing?

“sorry for being a real noob in grammar, but i am improving (i hope)”

Japanese sure loves to use double negatives, this is the grammar point that is notable for above:

https://www.bunpro.jp/grammar_points/86

If you want to copy sentences, you can use the “copy Japanese” button (on examples list) instead of copy and paste so furigana doesn’t get your sentences mixed up.

Here is the community grammar point discussion link below:

“Don’t have to wash the dishes” would be 洗わなくて (も) いい

@Kai and @Asher Thank you for providing your thoughts on たら and ば. I have updated both grammar points to reflect what you have discussed here and linked your comments to their relevant Readings sections. Cheers!

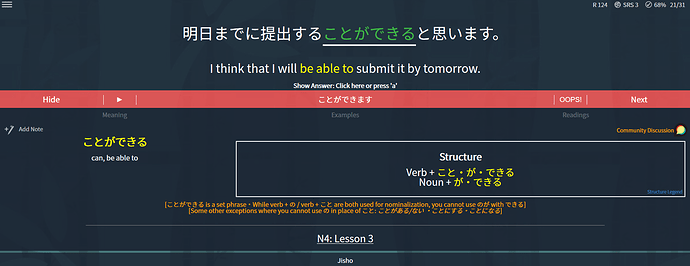

Hi there, I’ve got a question about one of the N4 points, this: ことができる

is ことができます a correct (I assume more polite) alternative? This is what prompted my question:

I thought the ます form suited it better since it was already using it for 思います, so I went with that one (usually BunPro tells us stuff like “more/less polite”)

Does it mean it’s wrong for ことができる?

I also found this:

https://www.thejapanesepage.com/100-grammar-points/dekimasu-can/

One of the sentences is

「日本語 を 話す こと が できます」

Lastly, if it is correct, aside from the difference in politeness is there any other difference? Can we use the two ます in a single sentence? Or is it odd?

Thank you!

@Kurei

Hey

Yes. you are correct!

However, politeness is usually expressed only at the end of the sentence.

If there is と思います、then there is no need to use polite forms in the other parts of it. So

明日までに提出することができると思います <- OK

明日までに提出することができますと思います <- generally not OK

Of course, ことができます is ok at the end of the sentence:

彼は泳ぐことができます。(He can swim)

There are some exceptions though, for example, if you have が (but) then politeness in both clauses (parts of a sentence) should be the same.

So only:

politeがpolite

shortformがshortform is correct.

難しいですが、頑張ります。

難しいが、頑張る。

But not:

難しいですが、頑張る。(though there are some rare exceptions when it works)

難しいが、頑張ります。

The same principle applies toけれども。

In the case of から、ので、けど, you can choose whether you want the first part of the sentence to be polite or not depending on how polite you want to be.

So:

politeから/ので/けどpolite - most polite version

shortformから/ので/けどpolite - a bit less polite, common

shortformから/ので/けど short form - least polite, common in casual speech

Of course, there are some other exceptions, like store clerks using polite from everywhere they can, direct quotations, etc.

I hope it helps,

Cheers!

Definitely clearer now! Thank you for the fast reply!

Also thank you for adding the part about the が/けれども exceptions to that rule!

I’ll start paying more attention to the difference in politeness between connected clauses (and to the different conjunctions).

Sorry for the delayed response here, but:

I don’t think 教える fits in with 見える・聞こえる at all actually, especially since it’s transitive (the intransitive verb “to be taught” is 教わる, おそわる). 僕にこれを教えて? also feels like a weird sentence (because why is an imperative being spoken as a question?), but at any rate would just be “teach this to me?” in English.

It just depends on the stress in your voice. Imperatives are quite often used as questions in casual speech (Although it would sound more natural with よ appended) なになにてよ etc.

Yes, I know it is transative hence why I wrote ‘to get taught’ not, ‘to be taught’. The focus is simply on a different person. It is also important to remember that Japanese do not actually have ‘transative and intransative’ verbs. Which I think is where a lot of the confusion comes from. You’re right that a better translation would be ‘teach this to me’, but this isn’t a translation, it’s a literal interpretation. And it literally means ‘Can I get taught this?’ (focus being on the teacher), thus showing your conversation partner that you need them to do something.

Forcing english concepts into other languages is a common theme in language teaching that only serves to confuse learners. There is a bomb playlist on Japanese grammar for Japanese middle school students that I will link to this post in the next hour or so. Many of the words we use to describe Japanese grammar are poor attempts to ‘link’ Japanese and English in ways that they frankly don’t need to be linked. And in some cases, ways that are impossible to link.

Edit: I should note. Being transative or intransative is irrelevant to what え does to verbs. All it does is show that there is a ‘getter’ and a ‘giver’. The が particle just shows the actor. We can reverse the が particle but keep the same meaning across many verbs.

教える- To get taught, (Teacher requires が)

燃える- To get burned, (Burned thing requires が)

The reason the が Is different is because the thing that takes に is only temporary, there is no guarantee that the action will continue. For 燃える に would be the thing that sets it on fire, but this may be only a one or two second event, while the burning object remains alight for a long time, regardless of the spark. For 教える に is being taught, but you cannot guarantee that the に focus is actually learning/engaged in the teaching. Hence why transatives and intransatives behave very differently in Japanese.

This first playlist is short but has some absolutely amazing short descriptions of why Japanese verbs conjugate the way they do (from a completely non-english perspective)

The rest of this guys videos are great too. He teaches a wide range of subjects.

This second guy is more widely known and also does amazing grammar videos.

His video about dissecting sentences with ね is amazing. I think it is one of the first few from memory.

Edit: If anyone else wants to check these out I highly recommend them. The second guy is much easier listening. First guy is a motor mouth so you may be pausing frequently to check the meanings of certain words hahah