That actually did clear it up for me a bit. Thanks.

私は犬が好きだからです。

Literally: “As for me, it’s because dogs are likeable things.”

Breakdown:

私は = “As for me” - I admit that translating は as “as for” usually sounds stilted, but it always provides an accurate meaning.

からです = “(It) is because”

犬が好きだ = “dogs are likeable things” - As others have noted, 好きis not a verb meaning “to like”, it’s actually a noun meaning “likeable thing(s)”.

Also, が always marks the subject of the sentence.

Usually?: No! ALWAYS!

When?: ALWAYS!!!

There are quite a few books on this topic, and this is just one example of a really good one. I actually think it can be beneficial to forget the concept of ‘subject’ and ‘topic’ when discussing Japanese. They don’t ‘not exist’, but they are absolutely not needed, almost ever. This is because sentence structure and auxiliary verbs etc etc paints a very clear picture of what is happening by themselves.

日本語には主語はいらない - Subjects aren’t needed in Japanese.

Anyway, I won’t preach the topic too much haha. If you ever feel like taking a read, I highly recommend this, and then having a bit of a closer think about what exactly a subject is.

This is quite incorrect. が does not always mark the subject.

Crepe is not the subject of the third sentence, it is the object of the verb 食べたい. The subject is Aさん, which is null (meaning absent, grammatically speaking) in this sentence.

Certain conjugations push even transitive verbs that would other use を into が (e.g. たい and 受身形). For example:

ご飯を食べる

Eat riceご飯が食べられる

Rice will be eaten

Neither statement contains a subject. ご飯 is the object of 食べる in both cases.

Also 好き is a na-adjective, not a noun. It might also surprise you to learn that in Japanese, adjectives have many of the same grammatical roles that verbs do in other languages (e.g. English).

But don’t feel too bad. These things are challenging early on. They become much more natural the more exposure you have to the language.

@Asher - Color me intrigued! That sounds like a book I’d definitely be interested in. If only my vocabulary was up to it!

What is up with the 文法が日本語を迫害している, though? Grammar is persecuting Japanese!?

There are actually quite a few books in this genre, the one I linked is one of the more tame ones that actually discusses everything scientifically. The 文法 that this particular book is refering to is more English 文法 than Japanese. It claims that the hype to ‘understand English’ has actually influenced the way Japanese grammar itself is taught to native speakers in regard to ‘subjects’ and ‘objects’ etc. All in an attempt to make understanding English easier later in life.

It also proposes that almost any sentence can be understood without difficulty due to the way auxiliaries are used in context with other particles. I think the way I have come to understand it (although my understanding is still far from perfect), is that every sentence has a は, and also has a が (or か). Through the context of the sentence itself, due to this information usually presenting itself, actually saying them is not necessary.

Some books even claim that native Japanese speakers have a 6th sense that speakers of other languages do not have (in terms if being able to read what a conversation is about)… Obviously these claims are a bit far fetched, but within the realm of the Japanese language itself, it holds a bit of merit.

As for this part, it kinda works like this -

は - Shows the absolute boundary for within which any statement can be made.

が - Gives a piece of information that is only a small thing within that ‘absolute boundary’.

か - Requests missing pieces of information that should fit within that ‘absolute boundary’.

I think this is the main reason people use が wrong far more often than は. Anything can be an ‘absolute boundary’, as the speaker themselves is the one who decides any given limitation. However for が, because it presents something as just a piece of something, it forces your conversation partner to guess what the ‘whole picture’ is.

This completely makes sense to me, and I think one of the biggest grammatical problems English natives have learning Japanese at first is trying to do the opposite: fit Japanese into English language categories. I know for sure I had (and even still have) that problem. “Subject” is a good example of such a category, incidentally. That’s why I endorsed Tae Kim’s perspective, despite how controversial it is. It led to some good conversation, at least.

That’s interesting. I’ve encountered that idea before, but since you would never actually speak that way, I wonder if it’s the right way to think about it? For instance, you would never say 私は私がアメリカ人だ.

This is addressed by the author of imabi.net in the Zero-Pronoun section of the Particle wa I page. This “zero-pronoun” concept is also known as a null-subject, which is a linguistic phenomenon of not only topic-prominent languages like Japanese, but also some Western ones like Spanish (because the verb encodes the pronoun, unlike English, which requires it as a grammatical subject).

Perhaps it’s merely a matter of preference, but I always found this explanation (null-subject) to be more natural and comprehensive. But it would be hard to say it’s fundamentally wrong to consider there’s a hidden が in sentences too, though. It might come down to how fully you want to articulate the grammar. Academics are very interested in that. Regular people rarely are.

I always find this kind of sentence interesting, because I think you’d get a 50/50 answer as to whether it is correct or not from native speakers (discounting that it is unnatural, and purely thinking about grammar).

As far as I know, は and が cannot ever be the same. Its kinda like trying to say one piece of a puzzle is equal to the whole.

For this to be correct

私は私がアメリカ人だ。

It would need to become something like

私はアメリカ人だが。

This may seem like a different が, but it is not. In the first sentence, が is stated as a fact within the overall picture being one in the same. It’s kinda like me looking in the mirror and saying ‘I am Asher’. The statement has zero value, as everyone involved already knows ‘I am Asher’.

However, in the second sentence, because I have presented that ‘I am american’ as a piece of info, rather than わたし, it automatically tells the listener that this is a piece of info about me, that is directed at them (as I already know that I am American). This is why this particular が translates as ‘but’, eventhough all it is doing is calling attention to your conversation partner that the info is directed at them.

Oh, interesting. I had always thought of trailing が・けど as cognate to trailing “but …” in English. In other words, I was under the impression が fulfilled a distinct grammatical role when preceded by a predicate. In the case of アメリカ人だ, this is a predicate, and thus a grammatically complete sentence (when properly topicalized) in Japanese.

So if I were to say, 私はアメリカ人だが、日本に住んでいる, is my living in Japan somehow a predicate of my being American? Or does this more in the direction of introducing new information? Just trying to get my hands around the idea it’s the “same が.” I get the impression that may be a key to understanding how Japanese people think about が, which I’d find very helpful.

It’s not so much a predicate as it is offering info about は. It’s one of those situations where ‘subject’ doesn’t work well for describing が. This can be visualized much easier if we do this -

私は日本に住んでいて、アメリカ人だが。

(The verb is simply a state within は, が is the only ‘important info’)

私は日本に住んでいるが、アメリカ人だ。

(Equally as correct, but now the verb is the important info.)

The only difference is that you are switching which ‘piece’ of information you think is the one that is more important to the listener.

Each sentence’s value changes based on who you are talking to, and what information they are likely to already know.

私は日本に住んでいるアメリカ人だが。

(This time everything after は is equally as important, as が presents the whole statement as something potentially unknown by the listener.)

Agreed. These are excellent examples of this difference in application, too. Thanks a bunch!

Sorry. I have to respectfully but strongly disagree. If you have something marked by が which seems to you to be a direct object, or anything other than the subject of the sentence, that’s a clue that you are not translating it correctly. You are thinking of the sentence as an English sentence written in Japanese rather than as a Japanese sentence.

In order to make sense of the grammar in that third sentence, there are three grammar points we need to understand which probably contradict what you were taught in school:

- が always marks the subject

- Verbたい (e.g. 食べたい) is an adjective, not a conjugated verb

- Adjectives can “go both ways” between “active” and “passive” forms (e.g. 食べたい can be either wanting to eat or wanting to be eaten)

I realize that 食べたい is usually presented as a “conjugated” form of the verb 食べる, which transforms it from “to eat” to “(somebody) want(s) to eat”. However, as stated above, 食べたい is really an adjective, meaning “wanting to eat/be eaten”. This won’t change how sentences are generally translated into normal English, but it does change how one understands the literal translations.

Below are some examples. In real life, many of these sentences would usually appear with the topic marked by は, and the null subject marked by が not shown at all, but for simplicity’s sake, I’ll just show the subjects.

Here’s a non-controversial sentence with an adjective.

彼が面白い = “He is…interesting.”

Here is 食べたい acting as an active adjective:

彼がケーキを食べたい = lit. "He is…wanting to eat cake ". When translated to normal English, this becomes, “He wants to eat cake.”

Here is 食べたい acting as a passive adjective:

ケーキが食べたい = lit. “The cake is…wanting to be eaten” = in normal English “(Somebody) wants to eat the cake.”

Here is 食べたい acting as a plain old adjective:

そのケーキが食べたいものだ = lit. “That cake is…a thing wanting to be eaten” or “That cake is…a thing (somebody) wants to eat”, which in normal English, becomes “I want to eat that cake” (maybe? It’s a somewhat contrived sentence, but 食べたい is clearly not a conjugated verb here, right?)

Bottom Line

If you think that が can sometimes mark a subject, and sometimes mark an object, then Japanese grammar becomes a confusing mess. But once you realize that が always marks a subject, Japanese grammar becomes almost perfectly logical.

If you think 食べたい is sometimes a conjugated verb, and sometimes an adjective, then Japanese grammar again becomes a convoluted mess. But once you recognize that 食べたい (or any verbたい) is simply an adjective, then the meaning becomes clear, and the way it changes form becomes uniform:.

For instance, here’s a typical adjective:

面白い = interesting; 面白くない = not interesting

And here’s 食べたい:

食べたい = wanting to eat/be eaten; 食べたくない = not wanting to eat/be eaten

See the consistency?

I recognize the literal translations are agonizingly awkward, but it makes me think of saying sorry in German. To say, “I’m sorry”, you don’t say Ich bin leidig (or something), you say Das tut mir leid, which is literally, “That does me sorrow”. If you thought that Das tut mir leid literally meant “I am sorry”, and then tried to decipher German grammar from that sentence, you’d end up mightily confused. I believe that most Japanese textbooks do something analogous with Japanese grammar, and it’s probably why so many people spend so much time arguing about it.

I suspect I agree with you, mostly. Once you get to a certain level, if you are still actively thinking about whether something is a topic or a subject, or if you are focusing heavily on grammar at all, you are likely missing the point of what you are reading. At some point, it just has to flow, and translating into or out of English means that your communication will remain unnatural and your comprehension limited.

That said, at the beginning, I found Japanese grammar to be incredibly inconsistent and confusing, and so much of what was being said seemed to be missing. Personally, I found Jay Rubin’s “Gone Fishin’” to be a revelation! Suddenly, so much of what had been confusing started making sense. It forced me to start thinking more and more about how Japanese grammar is generally taught, and how needlessly confusing it is. I spent quite a bit of time trying to decipher it, but once it broadly made sense to me, I realized I rarely had to focus on it anymore.

When I stumbled upon Cure Dolly, I felt I had found a kindred spirit. I didn’t always agree with her, and she definitely thought a lot more deeply about some grammar issues than I, but I admired her desire to let the masses know how truly consistent and logical Japanese grammar is. If I had found her 15 years earlier, I’m certain I would have saved so much time and made a lot more progress. But that’s me. I recognize that different people get hung up, or turned on, by different things.

I’ll see if I can chase down your book. It might not agree with me, and may be too in the weeds to interest me now, but I wouldn’t mind at least perusing it to see whether it makes anything more clear.

Here’s a non-controversial sentence with an adjective.

彼が面白い = “He is…interesting.”Here is 食べたい acting as an active adjective:

彼がケーキを食べたい = lit. "He is…wanting to eat cake ". When translated to normal English, this becomes, “He wants to eat cake.”Here is 食べたい acting as a passive adjective:

ケーキが食べたい = lit. “The cake is…wanting to be eaten” = in normal English “(Somebody) wants to eat the cake.”Here is 食べたい acting as a plain old adjective:

そのケーキが食べたいものだ = lit. “That cake is…a thing wanting to be eaten” or “That cake is…a thing (somebody) wants to eat”, which in normal English, becomes “I want to eat that cake” (maybe? It’s a somewhat contrived sentence, but 食べたい is clearly not a conjugated verb here, right?)

In my interpretation, what is happening here is that there are actually two ‘subjects’ in the sentence, but again it relies far too heavily on English grammar, and therefore get’s a lot of things mixed up. I would change it to this.

Here’s a sentence where we assume には is the speaker, and that ‘he being interesting’ is an opinion.

彼が面白い = “He is interesting -to me-”

Here we assume には is a group of people, in which he is the one that wants to eat cake.

彼がケーキを食べたい = lit. “He is the one wanting to eat cake (in the group)”

Here we assume には is the speaker, and that ‘wanting to eat the cake’ is an opinion.

ケーキが食べたい = lit. “The cake is a thing I want to eat”

Like above, here we assume は is the speaker, and that ‘wanting to eat the cake’ is a (constant/strong) opinion.

そのケーキが食べたいものだ = lit. “The cake is a thing I always want to eat”

The reason most of this is true is because い-Adjectives almost always used to require that a verb be conjugated with them, and in modern Japanese, they still usually do have a verb conjugated with them, that verb is just invisible.

For example, a full sentence using one of the half sentences from above.

私にはケーキが食べたく思っているが

Within me, wanting to eat cake, is what I am thinking.

が marks the adjective, 思ているが makes the whole statement as something about me worth conveying. The が is the subject of the thought, the person is the subject of the sentence.

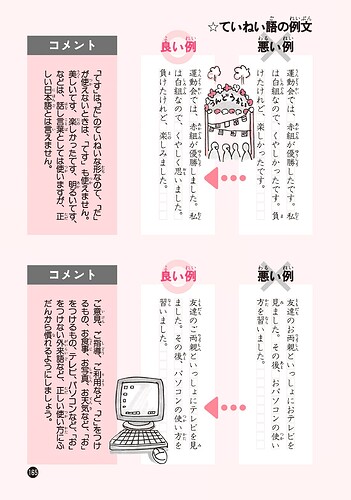

Edit - Just quickly adding a page from a book about Japanese grammar (for native speakers) to show why adjectives are subjects of thoughts/opinions, and not whole sentences.

While I understand where you’re coming from, and while it’s not completely without merit, it’s incorrect both for grammatical as well as conceptual reasons.

First, the sentence「クレープが食べたい」is not passive voice; it’s active. 食べられたい would be the passive. Appealing to English and German further demonstrates this, as English uses the auxiliary to be for the passive voice, whereas German uses the auxiliary verbs werden and sein. In both cases, the passive is expressed by use of an auxiliary and this is exactly the same in Japanese, where it’s 未然形 plus the auxiliary れる(五段)or られる(一段). ~たい, being a verbal auxiliary, assumes the voice of its host verb. If ~たい can be either active or passive, please tell me what the difference in meaning is between 食べたい and 食べられたい.

But there’s another reason why your explanation of the grammar doesn’t hold. When you express a simple SOV statement using a transitive verb as passive, what generally happens is the object is inverted into the subject, and the subject becomes transposed into an indirect object.「Aさんはクレープを食べる」becomes「クレープがAさんに食べられる」. Often, you can leave off the indirect object when it’s understood by context. The problem should be apparent.

If「クレープが食べたい」is a passive expression, then in context, Aさん would have to be the indirect object. That would result in the meaning of the sentence being, “Crepes want to be eaten by Mr. A,” but this is wrong twice over. First is that It’s the opposite of what we would understand in context. There, Mr. A is clearly expressing his will, not that of the crepes. Second, crepes don’t have will–they’re inanimate objects. Crepes can’t want to do anything. You can’t merely dismiss this as awkwardness of translation because there’s a fundamental cognitive dissonance here. I guarantee you no Japanese person thinks crepes want to be eaten by people. They, too, think people want to eat crepes. So why are we trying to torture the grammar into saying the former?

Finally, 形容詞 are verbs, or at least verbals (depending on definition). The fact the English word “adjective” is used to describe them is an merely an unfortunate historical coincidence (Japanese grammarians essentially looked for the closest English language part of speech they could find). I’m aware of no language authority who does not acknowledge 形容詞 exhibit all the categorical characteristics of stative verbs. Distinguishing them from 動詞 does not constitute a denial of this, it merely discriminates their unique qualities (動詞 can also be dynamic, not just stative). Both word classes can predicate sentences, and so therefore warrant being defined as verbs. I get the impression from your response that I’m somehow confused on this point, but it’s quite the contrary.

That concludes my thoughts on the topic. Feel free to take the last word.

But bunpro doesn’t really do literal translations, the translate the “spirit” of the sentence.

This is a slight tangent, but I was doing reviews at a study group this past weekend and there was some prompt where the highlighted hint was “every day” and the expected answer to fill the blank was に… and I was at a total loss for how に maps to “every,” and the whole group ultimately ended up in a discussion about how BP “localizes” their passages, rather than “translating” them, which feels accurate. In that case, highlighting “every day” was basically the best they could offer. And ultimately, I think localizing hints is for the best in the long-term for how you eventually comprehend the language, but it can make learning in the short-term very unintuitive

Correct me if I’m wrong, but wouldn’t the もん grammar point work in the place of だから (they carry the same meaning)?

犬が好きだから

犬が好きもん

Not an expert at all, but I think those could be equivalent in certain interpretations / contexts, but だから can indicate cause/effect, whereas I do not think that もん can…

(my rate of italics usage is inversely proportional to my self-confidence)

It’s also worth noting that the presence of だ/です in both of your examples is optional, and either statement can function in any of their three permutations (nothing/だ/です). i.e. もん、だもん、ですもの、から、だから、ですから

…I think. Someone should fact-check me; this is just my gut talking.

Do you know which textbook this is from?