What a wonderful thread!

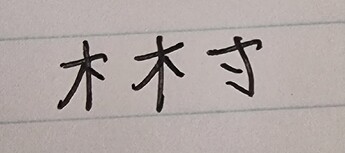

There are so many people talking about the practical value of writing kanji that I might incorporate it as well.

I had 2 runs for kanji.

The first one started on the fifth day of my Japanese studies and lasted around 30 days. I’ve spent ~90 hours on it, making up mnemonics in an RTK style. I was using SRS, and after some time, I felt tired. The situation got even worse because I couldn’t recall them fast, and stopping for 20 seconds in front of each kanji wasn’t looking good for me at that time. So my 1700 learned kanji meanings disappeared from my memory right after I gave up my SRS deck.

The second try has taken about ~70 hours. I was learning one 音読み for each kanji using, again, RTK order, to learn kanji with the same readings that come from a specific component. It didn’t finish well. I added 1500 kanji, but doing 5 hours of SRS per day was a bit too much, as well as though that “I don’t even want to read anything”. So I gave up again, and how one could imagine this route kanji-sound disappeared really quickly, as it was the only connection I’ve created.

Can not say it was the most productive time, but definitely was worth trying, never have regretted this my little experiment as well as the first one.

Recently, we’ve hosted a person whose language learning abilities were on a very high level, and the topic of discussion during that one week period was almost always going to hit SRS and Anki.

The main concept I’ve taken from those discussions is that “you have to take new and combine it with all you know, and all that is out there”.

To make the matter even worse, I’ve watched the first season of “Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency”, which made me like the idea “everything is connected” even further, and continued pulling me away from the idea of SRS, counting words, and working for numbers, as it provided only minimal connections, and wasn’t giving me the deep understanding that I conceptiually stared to seek.

The announcement of mock JLPT tests from the Bunpro team has awakened me from my sleep the night before the travel, and awakened the fire of looking for new studying methods, and not anywhere but specifically in Japanese.

That night I’ve slept only 2 hours, but instead I’ve come up with a new idea of “Holistic Approach for Learning Japanese”, where I would combine every little piece of information I have, and go deep into every little aspect of the matter to make it one a part of me, so I couldn’t lose it easily, and so it would serve as a massive fundament for a future learning.

The next day, on the 15 hour way home from Bulgaria, I was trying to combine everything I know to understand what I’m going to do with all of that.

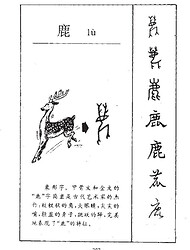

Trying to incorporate kanji as well, I was looking for something, and I stumbled across outlier-linguistics.com. With this website I discovered how interesting and fitting kanji with their etymologyes are in my picture of a world. The whole way I was reading different articles on the website, scratching the surface of the topic.

The first article was about differences between “radicals” and “functional components” and it’s hit me really well:

Kanji Radicals in Japanese. Don’t Do It. – Outlier Linguistics

When my plane was about to take off, I was buying their dictionary with etymologies. It’s still the best resource I’ve found in the language I can use.

I don’t know exactly how, because I was in a state of flow, but now I have my kanji learning setup that addresses most struggles I had with words, kanji, and recall in the past, and I can boast that it evolves every day.

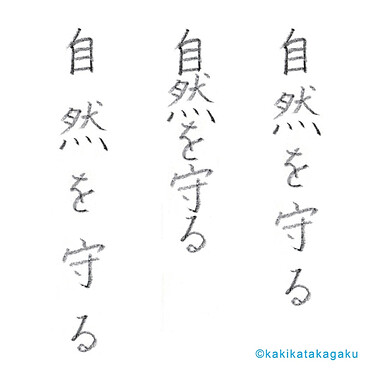

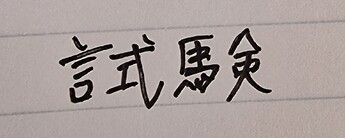

What I did was I took a deck with all the joyo kanji, and cleaned it up a bit, added a few new fields like “words” for words I know with that kanji, “tip” to write what I’m recalling, if it’s kanji’s meaning, onyomi, kunyomi, “note” where I basically put all the things I want to put there.

Now the whole process of learning works like this:

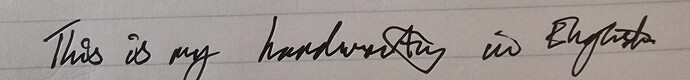

(everything happens on an iPad)

While reading, I’m looking up words in app yomiwa, which is a host for outlier dictionary, and if I think I’m familiar with kanji in a word (which is almost always the case for the time being), but I don’t know the reading, I look up the list of words with that kanji in the same app.

When I’ve found a word I know really well, that can be written using that kanji, I open Anki and find that kanji, adding that word/words in “words” field. This is definitely a very important step, as now, I don’t have to remember the reading, I just have to recall the word that includes that kanji, which is incomparably easier.

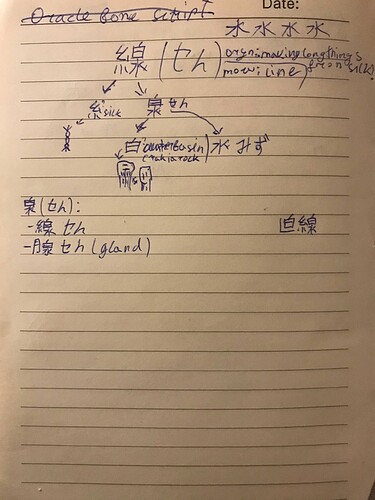

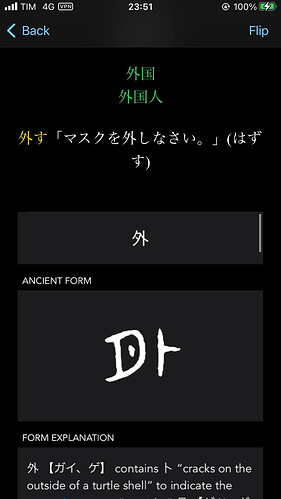

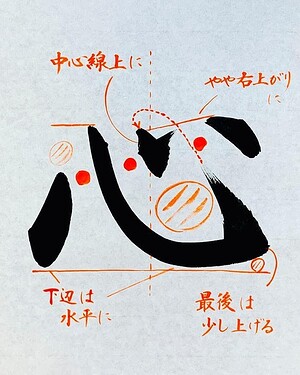

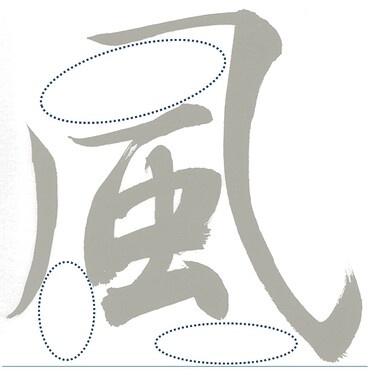

When I added enough words and I feel like learning kanji, I open anki and start doing reviews, when a new word appears, I try to research everything I can about it: etymology, type of kanji, its earlier appearance, components inside it and how they looked like, vocab, sentences, what are the other kanji with those components. Trying to ask as many quastions as I can. And adding some of that information in anki, less or more, based on how well I know the kanji and the associated word, so most of the time added stuff is only notes on which component gives sound, which component meaning, if there is one original meaning and form of the kanji, picture of old form/forms. This process usually takes 10 - 30 minues for each kanji, time needed depends on how well I know kanji, its components, word, averything else, and how much info I’ve got from my main sources. Somethimes it takes 2-3 hours but I learn a bunch of different stuff about China and probably understand the whole branch of kanji much better than before (before == non).

When I review cards and can not recall the card I do the same process (which goes much faster as I recall it imediatly when starting again) and trying to go further, because probably I forgot something, maybe what components mean, or I just have to understand the context of that kanji better.

So if we take what I usually look for it would probably look like this:

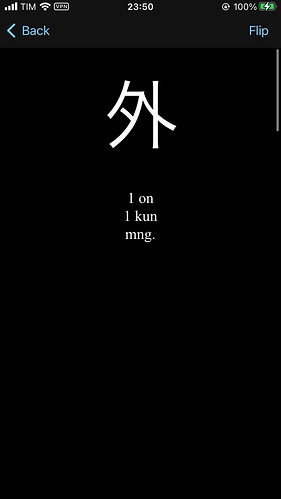

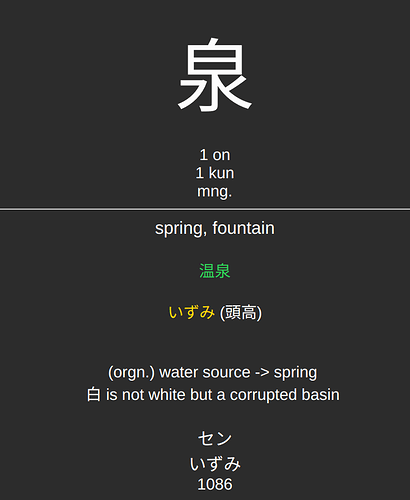

And cards usually and up like this:

or

Sometimes I just go through basic kanji like the first one above, because they are the most interesting and maybe/probably profitable to learn etymology, for many reasons.

So ye, I’m trying to make my learning process even deeper with every day, and if you have any ideas (maybe you know what my first screen is missing to make understanding even better), please share them, any feedback is necessary! (if someone has managed to read it though, because I just have taken a loot at this text and it’s actually huge!)

The more stupid the association, the better (お皿.

The more stupid the association, the better (お皿.  …)

…)