This is true, but one important thing to bear in mind is that when translating something to or from English, its word type can change. A common example of this is 好き, which is often translated as ‘to like’ , because that is the closest translation that works well in an English sentence. In Japanese it is a noun (or a な-adjective, which are nouns) however.

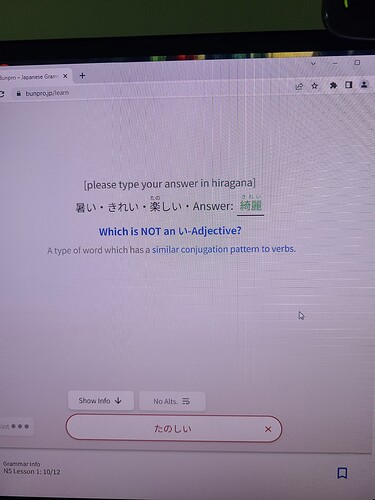

In your example question, 楽しい can maybe more accurately be translated as ‘enjoyable’, to show that it is an adjective in Japanese, and not a noun. I don’t think there is an equivalent word for きれい in the English language that is also a noun, so it is translated as an adjective. This does not change the fact that it is a noun in Japanese, and is conjugated as such.