So I’ve felt for a while that there is some fundamental way of thinking in Japanese that ends up affecting how they express things. Because I’m not accustomed to (nor aware of) what that might be, several sentences come off really weird to my brain. Some of these I’ve learned to get used to, but I’ll go ahead and post a compiled list of sentences I find weird, and why.

I’ll try to draw on common threads, but if you notice anything else, let’s discuss! The translations are not the question, it’s a matter of what underlying thought process leads one to express things in one way vs. another. So I’ll just put in a reasonable translation for each sentence (literal / natural). What would also be great is if we could add more example sentences for each “strange” phenomenon I list here.

In these examples, I explore the fact that Japanese conditionals often end in “it is __” instead of using a verb.

-

君と議論しても時間の無駄だ (Even if I discuss it with you, it’s a waste of time / It’d be a waste of time to discuss it with you.)

Comes off strange to say “if… it is X.” This happens a lot. -

何もせずに負けたら 好感度はカメムシ以下 (If I lost without doing anything, my likability is below an insect / If I lose without doing anything, my likability would drop to below that of an insect)

Notice that there is not even a verb to describe the likability dropping. And again, we have the “if…, then it IS” pattern, which I find strange. I’ll give one more example. -

もし照橋さんと鉢合わせたら 大騒ぎだな (If I were to bump into Teruhashi-San, it’s an uproar / There’d be an uproar if I bumped into Teruhashi.)

Again, the “if …, then it IS __” rather than using something like “would be.” Really strange, but I’m getting used to it.

Unlike the general trend to simply describe the state of a noun (see How to Learn from my Mistakes), here, I was corrected because I said Nであれば as opposed to Nしていれば:

- 「存在する人の行動が終了であれば、ただの過去形を使ってもいいですか」-> 存在する人の行動が終了していれば、ただの過去形を使ってもいいですか

Here, it’s weird to me that I can’t say 終了であれば. I asked about this later, and it seems that when using the conditional form, if the noun can take する, then you should use する in the conditional form.

This example shows a strange verb omission (from DeathNote):

-

日本の刑務所にいた人間が、一時間後にフランスなんて、 物理的に不可能だ (/ It’s physically impossible for Japanese prisoners to be in France just one hour later.)

To me it’s strange that he just says “フランスなんて” instead of “フランスに現れる” or just “フランスにいる” or something like that.

Using ない and ある on their own to refer to norms and expectations.

-

空いた食器を下げるとか あるだろ (Lowering empty dishes, exists y’know / Y’know, there’s that norm that you should lower empty dishes)

Here, the word “norm” or an equivalent is never used. It just says that such a thing exists. (So it makes me wonder if they just imagine a floating set of norms that you can point to as existing at any time.) -

ちょっと 聞いといて その言い方はないでしょ (Listen up, that way of talking, doesn’t exist right? / Listen up, you know that’s no way to talk, right?)

It’s weird that they say “言い方がない” to say that this is not an established norm/way of talking that conforms to societal standards that exist.

This is just a random example where I have no idea why ある is used instead of いる. I’ve checked multiple times to make sure.

-

私は今、キラ事件の捜査本部の指揮を取る立場にある (Right now I’m in the position to take charge of the headquarters for investigating the Kira case.)

Why not その立場にいる rather than ある?

Making hella weird commands:

-

嘘つけ (Go tell a lie / Lie more, why don’t ya?)

This is what someone said after they disbelieved what they just heard the other person say. -

This one’s a dialogue (to give the context):

海藤:な… 風邪くらい 誰でもひくだろ! (Kaidou: everyone catches at least a cold or something!)

斉木:まあ あいにくだが、僕は風邪をひいたことがない。超能力者だからな。 (Saiki (to himself): Well, actually, I’m a psychic, so I’ve never caught a cold.)

燃堂:オレ ひいたことね~けど。(Nendou: Well, I’ve never caught one…)

灰呂:そういえば、僕もひいた記憶がないな。(Hairo: Yeah, that reminds me, I too have no recollection of catching one.)

斉木:お前らは ひけよ (Saiki (to himself): Y’all, catch one.)

Really strange that Saiki just says “go catch one.” Then I asked about this, and a native Japanese speaker explained it like this:

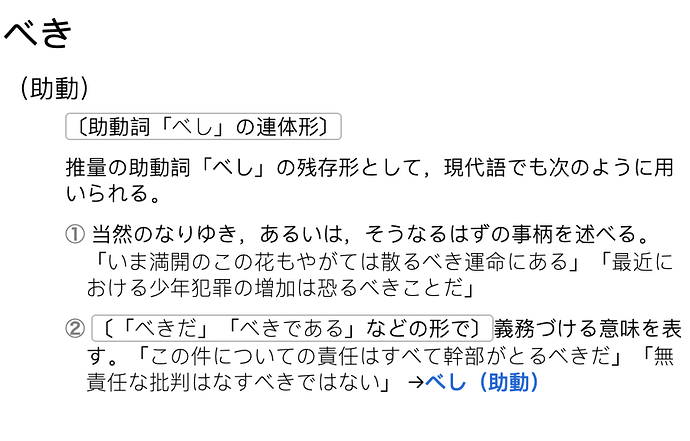

11) 燃堂と灰呂は超能力者じゃないのだから、風邪をひくべき (風邪をひくような体であるべき) (It’s that Nendou and Hairo aren’t psychics, so they should catch a cold, i.e.: their bodies should be of the type that catches a cold.)

The strange here is that he is using べき, which means “should” in the sense of what someone should do (rather than meaning “should” in the sense of a guess like “it should be the case that…”). This led me to create a different dialogue, which I was told was natural:

-

A: もしもし (Hello)

B: あっ、忙しい?運転中みたいんだ。 (Ah, are you busy? You seem like you’re driving.)

A: えぇ。気分転換ドライブだけだ。 (Yeah, just driving for a change of pace.)

B: えっ!運転しながら電話するのは交通違反でしょ。(Huh!? You know it’s illegal to talk on the phone while driving.)

A: 大丈夫だよ。全然警察に気づかれないから。(It’s fine tho. The police won’t notice a thing.)

B: バカ、このままじゃ他人を危険にさらすよ。 罰金を取られろよ。(At this rate, you’ll endanger others, dumbass. Get the fine.)

At the end, the command to get the fine was really weird to me, but it’s natural in this context.

There are certainly many more examples I could come up with. Feel free to add your own categories and examples of “strangeness” and let’s decode the Japanese way of thinking together!

)

)