There was a thread on this topic with a nice explanation by Asher last month which perhaps you’ll find handy. It is slightly baffling at first but you’ll get used to it over time. Tense in Japanese is a really fascinating topic overall but hopefully that linked thread is enough for you to go off.

I had to re-read this sentence in ch9 a few times:

礼子の子供のような屈託の無い顔に釣られたわけでも、その行動が可笑しかったわけでもなく、自分にとって想定外の出来事を前にして、ただ笑うことしか出来かったから。

First of all, that なく was sneakily negating both clauses before it, not only the second one.

But especially 前にして felt like I’m missing something here, until a search found it described as N1 grammar:

②人や物を表す名詞に接続して、目の前にあるものと対面していることを表します。その物事に対する緊張感を表せます。

So if I understand it correctly, the highlight here is that Koguma was a bit nervous about this new situation, and that’s why she only managed to react with a smile. Not because she mirrored Reiko’s smile or wanted to laugh at her.

Does this sound about right?

Yes, I think that sounds about right.

I think it says that it’s not because she was charmed by Reiko’s carefree child-like face, nor because of her funny (or weird?) behavior, but because she was “faced with” a situation “beyond her expectations”, that all she could do was smile/laugh.

I believe 前にして can be interpreted quite literally with 前に meaning “in front of” and then する as “do/make” and means something like “made to be in front of”. Like “be put in front of” in the sense of “made to face something”.

死を前にして would mean something like “faced with death” or “in the face of death”.

(As you can probably tell, English is not my native language, so please excuse me, if this does not make sense.)

Another general question about “complete” sentences in books.

I have noticed in this book, that many sentences seem to be somehow incomplete.

For example in chapter 10

sentence

顔を覆う透明なシールドの無いクラシックスタイルのヘルメット。

my translation

A classic style helmet, that does not have a transparent visor to cover the face.

This sentence does not have any verb, no copula and does not end with an い adjective.

I would have thought that this is an incomplete sentence and that especially in written language more exact grammar was required.

The author seems to use this kind of sentence quite often when describing things.

Is this common practice in books?

I would have expected something like である or だ at the end of the sentence.

Exactly, the idea of facing a situation, or being in front of a situation, does seem to correspond to this in English, and in my native language too. 緊張感, “feeling of tension”, is maybe not automatically implied, but depends on a situation… or maybe it is actually… Because whatever it is you are facing, you have to resolve before you can go back to doing what you were doing.

Perhaps what made を前にして feel strange when taken literally is that を? If it was not a set expression, then which verb would take 出来事を as an object here…

Hi!

Finished chapter 10. It is a strange coincidence that this chapter is named just as the chapter we are about to read in よつばと!.

Lots of vocab related to the road: 県道, 国道, 街道, 道幅, 舗装, 箇所, 余裕, 路上駐車… and, of course, to the bike. I liked the adverb 気の向くままに, at one’s fancy.

I have a doubt about the sentence:

とりあえずホームセンターで買うような洗剤や生活用品は足りているので、左手のスーパーに向かう。

So she heads to the supermarket on the left-hand side as she has enough detergent and daily supplies, (the type of things) that she would buy in a hardware store, for the time being!?

Yes, I think that’s what it means.

Yes, the を seems to be good indicator that the 前にして is itself a verb-like fixed expression.

Otherwise, I would have expected の前 instead.

The same thing happens with other such grammar structures like

Finished chapter 10.

Before starting this book, I would’ve never imagined that I’d worry about the protagonist not because she is about to be blindsided by a dragon attack,

but because

she might not be able to load all groceries on a scooter

Finished chapter 12.

My brain didn’t want to brain today so I struggled a lot. Thankfully, chapter 13 appears to be very short. Can’t believe we’re already over 25% of the way through the book.

制服が風でバタつくのが気になるけど、自らの動体視力や三半規管が、速度に比例して増す入力情報を受け入れていることはわかった。

Me trying to understand that entire sentence.

I mean I think I kind of get it. Maybe…

Hello! I’m not taking part in this book club, but I pop in now and again to read the comments and wanted to take a crack at answering the question you had here.

The sentence you’ve quoted here uses a relative clause to modify the noun ヘルメット. If you used the genki books, this type of sentence is described briefly in Genki 2. Tofugu has a write up about clauses here. If you cmd + f “relative” it’ll take you straight there.

Someone else almost certainly has a better capacity to explain how and why this works but I’m fairly confident this is at least what’s happening in the sentence.

I did find this sentence a bit clunky too.

I think, in the context, that Koguma’s doing a speed test, it’s sort of setting the vibe by using sciencey jargon (e.g. 動体視力 / 三半規管 / 入力情報 )

How I parsed it

A けど、Bはわかった。

A but she learned B.

With

A = ‘She was worried about her uniform flapping in the wind’

B = ‘ones eyesight and hearing accepts information increasingly in proportion to your speed’

Does that roughly match how you read it? (I could have misparsed it, so I could be miles off!)

That’s also how I interpreted it.

(along with google and DeepL because I thought I must have missed something after I read it)

This week doesn’t have any new proper nouns, but there is an allusion to the Straw Millionaire in Chapter 12.

Also, as we’ve been reading for a month now, I think it would be a good time to check in and ask about the reading pace.

Thank you for the link. Very interesting.

The sentence that modifies the noun, which often corresponds to a relative clause in other languages, is actually not the thing I was wondering about.

If you take away this “relative clause” then the sentence that is left is just:

ヘルメット。

I know that in spoken Japanese, you can omit almost everything from a sentence.

But I had thought that in written Japanese a complete sentence would always need one of the following things at the end

- a verb

- an い adjective

- a copula (です, だ, である, …)

- probably missing other valid options?

and optionally a sentence ending particle like ね, よ, etc.

I thought just a noun alone was not a complete sentence (in written Japanese).

But the Tofugu article actually has the example

(それは)犬。

So it seems like my thinking was incorrect. (Or maybe this is for spoken language?)

Usually, when you have some kind of embedded sentence that ends in a noun, you will need the だ or である, so I thought this was also true, for the end of the outer sentence as well.

I think that

これは犬と思う。

is incorrect and it needs to be

これは犬だと思う。

But apparently, its okay for the whole sentence to end with just a noun?

I noticed the author does this a lot too, and sort of took it to be setting the tone as fairly conversational.

It gives me vibes of a string of texts where you’re omitting stuff as it’s a flow of information.

In other things I’ve read, I’ve also seen similar when an object suddenly springs up, and it’s maybe emphasising the object.

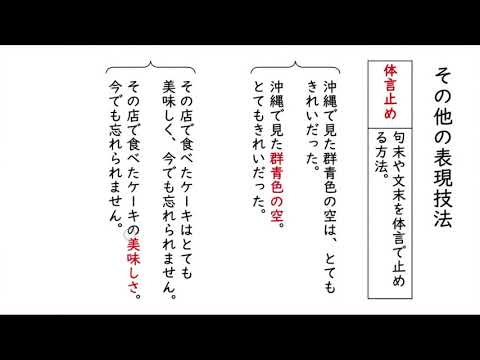

I think this might be called 体言止 , I wouldn’t be suprised if it’s the kind of thing which stricter grammarians(?) frown upon, but is a part of the language nonetheless.

Edit: Added in this (Japanese only) video, which I think is what is happening

Hi!

I think so too. 私にとって, the pace as first established in your guide is good.

Thank you for this!

Well hey at least we got a 動体視力 and not something like ダイナミックビジュアルアキュイティー

Thank you for your reply and the links!

体言止め seems to be what the author is using.

I also get this feeling of “a flow of information”.