That’s a very informative graphic!

Thanks for this great explanation ! I think I understand the てきた part.

I still have a few questions :

- Is お金がなくなっていてきた also a correct way to say “I have started to lose money” ?

In your picture you show that お金がなくなっている can mean :

- I am losing money

- I have lost my money

How is this possible to distinguish between the two then ?

I thought that “I have lost my money” would be translated as お金がなくなった.

I’ll add my two cents based on how I’ve learned it. Maybe it helps, maybe it doesn’t.

I’ll put the long answer first and answer your questions at the bottom…

=======

When thinking of these grammar points, you’ll have to shift your thinking a little bit to think about where you are relative to the action or the state of the action.

Vている - this is showing that you’re in the state of verb, which is often translated as (verb)ing but not always.

走る - I run / I will run

走っている - I am running / I am in the state of run(ning)

Sometimes time words help modify the meaning:

きょうは 走る。 I will run today. (future tense)

まいにち 走る。 I run everyday. (present tense)

Vている - this is translated as past tense and not as (verb)ing when the verb is instantaneous and cannot be continued.

おまえは もう死んでいる。 You are already dead. You are already in the state of die.

========

Vてくる - this is showing that a verb has come to pass, has come to you, which is often translated as “has/have started”.

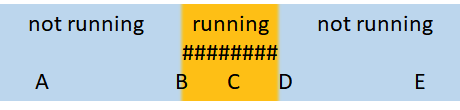

Like in nekoyama’s pic, it started in the past and has continued until now.

走ってきた。 I have started running. I have started to run.

========

A. きょうは走る。 I will run today.

A. 今走っていない。 I am not running now. I am not in the state of running.

B. 今から走る。 I will run now.

C. 走っている。 I am running.

C. 走ってきた。 I have started running. I have come to start to run.

D. 走った。 I ran.

D. 走り終わってきた。 I have finished running. I have come to pass the end of running.*

E. もう走った。 I already ran.

E. 走ったことはある。 I have run. I have the experience of run(ning).

'* Some of these are really difficult to properly translate but I’m just trying to show where the grammar points are used relative to the action.

'* Basically, I don’t think I’ve ever heard ている together with てくる.

===============

I think you’re trying to make it fit a 1-to-1 translation.

お金がなくなっていてきた。 (This sounds awkward because it sounds like you know you’re losing money but also you just realized you’re losing money?)

お金がなくなってきた。 I have started to lose money

There’s no distinction (without time words). You are presently, right now, in the state of お金がなくなる (become to lose money). If you are describing your present scene as “I have lost my money”, then it is the same. However, if you are thinking of a past event and say “I have lost my money”, then you would use something like お金がなくなった or お金がなくなってきた.

お金がなくなった means “Money disappeared” or “I lost money”.

お金がなくなってきた means “Money disappearing has come to pass” or “I have lost money”.

One more thought: I think if I had to describe the situation where I’m in a casino, and I’ve only been there 5 minutes but I’ve already started losing money, I would say…

お金がなくなる ことが もうなってきた。

お金がなくなる ことが もう始まった。

The money-losing-thing has already come to pass / has already started.

I have started the money-losing-thing.

I already started to lose money.

Thanks for taking time to explain ! I think you are right when you say I try too much to fit the english translation. Usually I try to translate myself the sentence literally to better understand the logic of the grammar than just taking the translation as it is. Most of the time it helps. Sometimes the “proper” translation can be a bit misleading for a good grammar understanding, even more as english is not my native language.

I read again lessons about ている, くなる and てくる and it seems that I was wrong in my understanding of ている and てくる.

I keep trying to use くなる ( ~になる・~くなる | Japanese Grammar SRS )during the reviews for this topic.

Can someone please explain to me the difference between the two, or when one would be used over the other.

The main review question I keep getting hung up on is the following

私はアメリカに帰ってから、どんどん------- [太る]

With 太ってきた。being the accepted answer. My question is mainly what is preventing something like 太くなった from working.

I learned くなる first so it’s what my brain jumps to first and I’m having a hard time even keeping this review in my head as an option. Please help thanks

Well, in the specific example you gave, 太く is not grammatical.

太る is a verb, not an i-adjective, so it doesn’t inflect with ~く. There is a 太い i-adjective that would inflect as 太く, but Bunpro is wanting to test your ability to conjugate 太る (a verb) to mean “came to be fat.” That’s why [太る] is supplied in brackets after the example sentence.

As for the difference between 太くなった and 太ってきた, the main distinction is spelled out pretty well in @nekoyama’s reply a few back. Take a look at this excellent diagram:

The key thing is the note at the bottom:

~くなった implies having reached a state or condition at a point in time, whereas ~てきた has more of a progressive, ongoing feeling to it, especially when paired with どんどん here. The idea is something already started, it progressively came to be that condition, and it may or may not go on being that way. That might be kind of a sloppy way to put it. In fact, there are at least four or five distinct senses in which ~てくる can be used, I just didn’t want to belabor the point too much because it might be more confusing, not less.

I’m not sure I understand what you mean. Are you trying to tell me that てくる is used on verbs and くなる is used on adjectives? Because if so then that makes sense and I think I got it now. If that’s now what you’re trying to tell me please let me know because I don’t want to learn it wrong.

So in the example sentence that I was struggling since fat was being used like a verb and not a describing it becomes てきた ? Am I getting that right

But if they were saying someone is fat then you could use くなる because it’s not something that is happening?

Well, no, that’s not quite what I meant. I was trying to answer this part of your prior reply:

The answer to that question is Bunpro wants you to use the verb 太る in your answer. That’s why [太る] is in brackets at the end of the example sentence. 太く is not a grammatical conjugation of the verb 太る, and 太くなった uses the i-adjective 太い instead of the verb 太る, so it’s not the correct answer.

太くなる means “to become fat/thick” or “will become fat/thick.” To mean “is fat” you’d use 太っている. I could be wrong, but I don’t think 太い is used to mean fat as in corpulent (i.e. having a fat body). I think 太る is used for that. 太い tends to be used for cylindrical objects. You could describe someone has having 太い腕 (thick arms), for instance. So that would also be a semantic reason 太くなる would not be used in this context.

Does that help to clarify?

No it does not help clarify. Thank you for your time but I think we should just drop it. I’m sure it’ll just come naturally at some point. I don’t care about the word 太 I am just trying to grasp how a grammar point works. Thanks anyhow

OK, sorry I couldn’t have been more help.

I think your instincts are right. I’m sure you’ll recognize the usage with enough expose.

You’re trying to use the i-adjective conjugation with a verb, which isn’t how this bad boy works. In the ‘Structure’ section you can see the following:

[な]Adjective + に + なる ------- so, you take your na-adjective and add になる to make the point

[い]Adjective[く]+ なる ----- so, you make the i-adjective into ku-form (i actually have no idea what it’s properly called lmao, just replace the い with く) and then add なる.

These 2 methods cannot be used with verbs. With verbs, you would do this:

Verb[て]+ くる — make the verb into て-form, then add くる to add the meaning of ‘To come to, To become, To continue, To be starting to, Has been ~ing’

So, going back to your original question, you would see the verb in brackets and (theoretically  ) know that it has to be conjugated like a verb. I’m sure someone could explain this a lot more in depth, but that’s probably the gist. What @wrt7MameLZE33wlmpCAV wrote though is really important and worth a second read in the future as it will help reinforce knowledge of adjective conjugation. Let me know if anything is still tripping you up.

) know that it has to be conjugated like a verb. I’m sure someone could explain this a lot more in depth, but that’s probably the gist. What @wrt7MameLZE33wlmpCAV wrote though is really important and worth a second read in the future as it will help reinforce knowledge of adjective conjugation. Let me know if anything is still tripping you up.

After learning about てくる and てきた in the details of this new grammar, in the first quiz the solution is てきて. However, it’s not explained anywhere when I should use てきて instead of てくる and why.

Could you please add that, or am I missing something?

Which sentence was it?

-

すぐ帰ってきてね。

-

お弁当を持ってきてください。

-

朝から家の掃除をしていたので、家が綺麗になってきている。

#1 is a casual imperative, #2 is conjugated ~て to connect ください, and #3 is conjugated ている per the typical rules of that grammar point.

It was sentence #1. When is the casual imperative introduced? I’m taking the JLTP path and I don’t think I’ve come across this one yet.

The polite request is introduced at N5 L9, with a note that ください can be dropped to become casual.

The casual request is at N4 L6.

てください | Japanese Grammar SRS

Verb[て] | Japanese Grammar SRS

In the English sentence, there is no “please”. So don’t know how I should know that “てください” is needed here:

“Come back home soon!”

Sounds more like an order than a request.

The English “Come back home” could be translated as either:

“帰って” or “帰れ” (request or imperative forms).

…but they each have very different feelings that go with it.

(I’m skipping the きて part for this explanation)

帰って-- we’re excited to see you again so we want you to come back home [said to a friend or family]; the listener is totally free to decline if they are unable/unwilling to do so.

帰ってください – this is the polite version of above, and to show in English that it’s polite, we translate as “please come back home”, but it’s still a request and not an imperative demand.

帰れ!-- you’d better come back home right now or you’re in big trouble; the listener is not being given an option to decline.

As far as passing the quiz, Bunpro tries to give context to help understand which form fits the quiz, but like this, it can be ambiguous sometimes. For this case, it’s more normal to use the request form 帰ってきて because there’s no indication that the speaker is angry and there’s no emergency. There’s also ね at the end to indicate a friendly tone. Using the imperative 帰れ would be rude or not make sense in this context.

@FredKore, thanks for your explanation. The one option I chose isn’t part of your explanation though. It’s simply 帰ってくる. Just the basic form that I just learned.

Therefore, my comment was only about mentioning that it’s not really clear why くる instead of きて is incorrect here. Typically, if multiple answers are correct, Bunpro accepts all of them.

Well the reason it’s not 帰ってくる is that that isn’t a command.