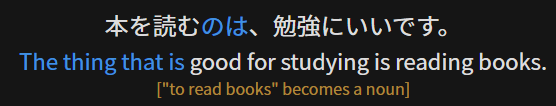

Could someone please explain this to me? The verbs still act and feel like verbs.

I don’t understand how this for example is now a noun. It still says reading, which is a verb. I understand how this thing is used and how it changes a sentence, but I just don’t understand what it actually is, which makes it frustrating.

There are three things to say here:

One - You should read about gerunds in English as it may help you understand better. Consider the sentence “Reading is difficult” - “Reading” is acting as a noun and is being attributed with the adjective “difficult”.

Two - English and Japanese are different so no matter how literal the translation things will be grammatically different when expressing the same idea.

Three - The thing after the verb is the noun and the verb (or verb phrase) before it is describing the noun. E.g., 読むこと = “the abstract thing that is reading”. In English we just use the gerund “reading”, normally, in such cases.

本を読むの would be parsed more or less as “the reading of books”, right? So don’t think of it in terms of a gerund, though when you nominalize a verb it usually looks kinda like a gerund. However it works as a noun. I guess the example sentence makes it look like it remains acting as a verb, but that’s the case of the translation, not of the sentence in Japanese.

The sentence, taken more literally, would perhaps be something like “as for the reading of books, it’s good for studying”, if I’m not wrong.

I’m pretty sure you’re having the same misunderstanding I was having when I first learned verb nominalizers in Japanese. I’ll try and explain this with English examples, and then move to your example sentence.

If we look at how “-ing” works in English we see that it turns a verb into an action - ‘reading’ is not a verb. Using the English translation of the sentence you provided as an example - “The thing that is good for studying is reading books.” It may not seem like it, but if you break apart this sentence, “reading” is an action, while “reading books” is a noun. If we look at another example such as “I like reading books”, we see here that reading is not a verb. Looking at it closely we see that “reading” is simply an action being done. Not to mention, right before it is the verb “(to) like”, and we know that verbs don’t act on verbs. Breaking this down one step further, all verbs with “-ing” added onto them are simply actions. What is an action? it’s either “a thing done”, or “doing something”. Therefore, if we look at “doing something” we see that the word ‘doing’ is an action, while “doing something” is a noun. If an action is “doing something” and “doing something” is a noun, then we know that an action is a noun; either it’s a thing that is in the process of being done, or it is a thing that is done. So theoretically an action is a noun (I’m mentioning this just in case someone really wants to be critical of how のは nominalizes verbs and comparing it to “-ing” in English).

Now, if we go back to the Japanese sentence, we have 本を読むのは、勉強にいいです. Looking at the first part of the sentence without のは we have “本を読む - to read a book”. Here we have 読む which is a verb, and that verb is acting on 本. However, when we add のは to get 本を読むのは we now have “Reading a book”. Taking what we learned about “-ing” in English, we see that this whole phrase has now been nominalized to be a noun. Reading a book is not a verb, it’s a state of doing something, and a state is simply a noun. Once again, you cannot verb a verb, so if you were to say “I am reading a book” reading cannot possibly be a verb. This is why if you were to say “I am read a book” it makes zero sense, because you cannot be in the state of “read a book”.

Hopefully that helps. I realized I wrote a bit too much, but I don’t really know what to change. It’s really just reiterating that “-ing” in English is not a verb, it’s an action, and actions done to something make that phrase a noun.

I think part of the difficulty with this particular example sentence is that the English translation does not very closely mirror the Japanese original.

I would suggest focusing on the original Japanese and trying to fully understand what is going on there, rather than trying to ‘harmonize’ it with the English translation – if you look at it Japanese-first, then I think you will see that the English translation is very much secondary, and is basically a compromise to make the English seem more natural sounding.

Japanese-first interpretation of the grammar of the sentence

The first thing to realize is that what is happening in these ‘verb nominalization’ grammar points is actually an application of a much more basic grammar function, which is ‘noun modification’ aka 連体形, ‘rentaikei’, technically known as the ‘attributive form’.

This attributive/rentaikei form is simply how you attach one word in front of a noun, to modify the noun.

You are already very familiar with the attributive/rentaikei forms of い-adjectives, which is just the standard form ending in い, such as かわいいねこ = cute cat.

連体形 (rentaikei / attributive form) essential structure

Basically, it’s: [word in rentaikei form] + [noun] = [modified noun]

All you have to do to use this properly is to know how to turn different types of words into their respective rentaikei forms. And actually, that’s pretty easy, and you probably already know all of them. But for completeness, I’ll just list them here:

| Type | 連体形 | Example | Example + Noun | Modified Noun Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| い-Adjective | [い-adj] | かわいい | かわいいねこ | a cute cat |

| な-Adjective | [な-adj]+な | げんき+な | げんきなひと | a healthy person |

| Noun (aka の-Adjective) | [noun]+の | えいご+の | えいごのせんせい | an English teacher |

| Verb | [verb] | よむ | よむほん | a book to read |

Note that the 連体形 for a verb is just the verb itself. You simply put the verb in front of the noun, without changing the verb, and it automatically modifies the noun. [Incidentally, this is also why い-adjectives are simply placed in front of nouns without modification, as technically they are verbs (or at least verb-like) in this respect – note how い-adjectives can also end sentences without だ or です as well, just like verbs.]

How this relates to ‘verb nominalization’?

From a Japanese-grammar-first perspective, when you are ‘nominalizing a verb’, what you are actually doing is just ‘modifying a noun’, by using a 連体形 word, and in this case that 連体形 word happens to be a verb! And the 連体形 form of a verb is just the verb itself!

So, to re-examine your example sentence, the Japanese-grammar-first perspective is to look at the noun first, which in this case is the word の.

This の is a being used differently from the の particle used in the 連体形 form of a noun. Instead, it’s taking the place of an unspecified noun, and acting like a noun in its own right. You can think of it like the English words ‘it’, that’, ‘thing’, or perhaps most memorably as ‘one’ – as in, “(the) one (that)” or “(the) one (which)” – since ‘one’ is similar to ‘no’ aka ‘の’.

However, for the sake of your example sentence, I would suggest the best translation would be the word ‘that’, specifically in terms of the phrase ‘that (which)’ or ‘that (which is)’.

So, with ‘の’ (‘that (which is)’) being the noun which is being modified, what 連体形 word is modifying the noun? In this case it is the verb ‘読む’, ‘to read’. But more specifically, it is the full verb-phrase ‘本を読む’, ‘to read books’.

Thus, the full, modified noun in question is ‘本を読むの’, which – again, from a Japanese-grammar-first point of view – can be thought of as:

[連体形 word/phrase] + [noun]

= [本を + 読む] + [の]

= [book + to read] + [that]

= [to read books] + [that which is]

= [that which is ‘to read books’]

Therefore, if you were to really translate the sentence from a Japanese-grammar-first perspective, it should more closely read as:

本を読むのは、勉強にいいです。

= [本を読むの] + [は] + [勉強に] + [いい] + [です。]

= [that which is ‘to read books’] + [regarding] + [for study] + [is good] + [polite copula ~= ‘is’]

= [regarding that which is ‘to read books’] + [is good for study] + [(it) is]

Now, this is the sentence from a Japanese-first perspective. However, it’s a little clumsy to further translate it into natural-sounding English. So, IMHO, they decided to further translate it into something more natural sounding, by using the common English idiom, “The thing that is X for Y is Z,” like, “The thing that is good for a cold is chicken soup.”

This transition requires changing the order of things from the Japanese ordering, so you get:

[regarding that which is ‘to read books’] + [is good for study] + [(it) is]

= [(It) is] + [is good for study] + [regarding that which is ‘to read books’]

But now it really doesn’t flow like the idiom, so they kind of have to twist things here and there to fit it into the English idiom, but in the process kind of jumble up where the original meaning came from from the original Japanese sentence:

= [(It) (The thing that) is] + [is good for study] + [regarding is that which is ‘to read books’]

= The thing that is good for study is that which is ‘to read books’.

Now notice how ‘The thing that’ and ‘that which is’ are both referring to the same thing, namely the action ‘to read books’. But because of the shuffling of the English idiom, the original ‘that which is’ (from the original word の) has now been shifted to the end of the sentence, but the indirect reference to it (associated with the original word です) has been shifted to the front of the sentence.

I believe that is the primary cause of confusion. In effect, this shuffle/swap has disconnected the noun-ness of ‘that which is ‘to read books’’ and split it up into two parts in the English translation, 1) “The thing that”, which is very noun-like, and 2) “that which is ‘to read books’”, which is more verb-like.

This initial separation is then further confounded by the introduction of an English grammatical construct called a gerund (see link and other discussion above), in order to make the translation sound even more natural in English. However, it becomes even more confusing because they did this both for the noun ‘study’ (勉強) into ‘studying’, and also for the verb ‘to read books’ into ‘reading books’. It makes the noun ‘study/studies’ more verb-like, but it disguises the fact that the ‘to read books’ was never a verb on its own, by making it seem more independent as just the verb-sounding phrase ‘reading books’.

= The thing that is good for studying is that which is to reading books.

= The thing that is good for studying is reading books.

If we were now to ‘untranslate’ this back closer to the original Japanese, it would go like:

[The thing that …] + [is good] + [for studying] + [… is] + [reading books]

= [reading books] + [for studying] + [is good] + [The thing that …] + [… is]

= [本を読むのは] + [勉強に] + [いい] + [です]

But now it is clear to see that “[The thing that …] + [… is]” is occupying the place of “[です]”, which is a side-effect of trying to jam the original Japanese into the English idiom. It sounds more natural in English, but you have this extra “The thing that is” that seems to have popped out of nowhere.

Conclusion

My main point in going through all this demonstration is to highlight that I don’t think the real issue is that ‘[verb] + の’ is turning the verb into a ‘gerund’. That’s an English-grammar-first interpretation. And it isn’t even so much that の is ‘nominalizing’ the verb. It’s more that の is acting as a noun in its own right, and sticking a verb in front of it is actually just modifying that noun の, according to the standard practice of [連体形 word/phrase] + [noun].

What has made the whole thing confusing is the attempt to make a natural-sounding translation into an English idiom which 1) shuffled the order and inadvertently disconnected 本を読むの into two parts, “The thing that” and “reading books”, and b) introduced English gerunds where the Japanese did not have gerunds, replacing a more accurate translation of “That which is ‘to read books’” into a more natural, but a bit misleading “reading books”.

Thanks for this! Now, thanks to another explanation by josh, the entire gerund thing has actually turned into a way of explaining how it is more noun-like. I read that one first, so the later part about how “reading books” and “studying” sounds more verb-like is now something I don’t see.

This post helped me with understanding how English grammar should not be the first perspective to look at things from if you wanna understand it unless you can find a way to do it as josh did, and also taught me about rentaikei. I didn’t know about this until now. Thanks for introducing me to it!

This was a big help. I can see how those actions function as nouns. That was actually what I needed!