That is very impressive. Good job!

Now excuse me while I add that to the list of things that I will never do

諦めるな!

Well done sticking to your process day in and day out.

I had originally discounted trying to learn writing kanji, as I’d never actually need to type them by hand. But your post gave me a new perspective on the topic - gaining better recall and recognition among visually similar kanji through physical practice. It looks to me like a worthwhile venture now.

How do you go about your daily session? I imagine you write by hand a given kanji a certain amount of times before moving on to the next one. How do you incorporate readings into this? Also, you mentioned you did them in grade school order. I imagine there’s one standard order that’s listed publicly?

Looking forward to the three years post ;D

@Gabrielkarrer @jbrommehd @Slackware

I think this kinda answers all of your questions in some way

I just recite the readings as I am writing, verbally. Usually I recited every reading once for each time I wrote the kanji. 生 is probably one of the few kanji where it takes longer to recite the readings than actually write the kanji, but I still made sure to do it.

As for differentiating each reading’s nuance, I never did that, as that differentiation comes later via similar kanji (usually). I just assign the one word to every reading (‘life’ in the case of 生), and then learn any nuances later.

For example -

生きる、生ける、生かす

Is seen again in

活きる、活ける、活かす

So the nuances of life and livliness become clear.

生む、生まれる

Is seen again in

産む、産まれる

So the nuance of birth and being born become clear.

生る、生す

Is seen again in

成る、成す

So the nuance of to become whole/bear fruit become clear.

生える

Is seen again in

映える

So the nuance of projecting outward becomes clear.

I always let common readings like this be what taught me the nuance, rather than trying to remember an English word for each one.

There are exceptions of course, like - 生やす, but if you already know 生える, it is just the transitive version of the same thing.

I wrote each one down around 10 times, while actively thinking about other kanji that share the same reading, and how they differ in regard to nuance. There are quite a few kanji that don’t share common readings with any other kanji, but these ones are usually fairly easy to remember, as they have their own unique personality which is reflected by their keyword, without needing to worry about the extra nuances.

As for the school level list, I believe the 常用漢字 wikipedia page actually has the list in order. Several public anki decks are also fiterable by school grade order.

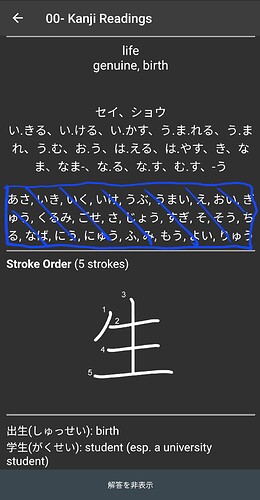

Here’s what the front vs what the back of my deck cards look like. I didn’t bother learning the readings in blue at all, as they are only readings associated with names, not words. I also didn’t bother (actively) learning the list of words that use that kanji, apart from the main readings. So the list of words at the bottom is just a reference that I sometimes glanced at/made a mental note of, but didn’t put there myself. They came as part of the deck.

For kanji compounds, namely when you’re using the onyomi to create compound words, I just learned these in the wild. I think because I had a really really strong foundation of the core kanji meanings, I really only needed to see compounds once or twice before I knew them.

When I saw the side with just the kanji, I would recite all the readings once in my head before revealing the answer, and starting to write.

That’s been my experience as well, just working through WaniKani. Once I started putting in the extra effort to create a more vivid mental image of the kanji and solidly memorized meaning and reading, compounds became a breeze to learn (exception being the oddballs here and there like “carrots”, for some reason, where kanji meanings add up like 1+1=3). Over time, I even started noticing patterns of when sounds get dropped or rendaku happens (I know there’s a useful Tofugu article on that, which I have yet to read).

Recently, I’ve been toying with the idea of “attaching” the kunyomi reading to the kanji, instead of a specific vocab word. That’s been useful too so far.

@Asher , thanks for the explanation. Details like focusing on all the readings while sticking to a single kanji meaning and not mixing in the vocab meanings was really useful.

I’ve a follow up question, tho. How do you identify words that are just nuances of the same concept. Is it as clear cut as “same reading + slightly different kanji meaning”? Are there cases where the reading is the same, but the words have no connection whatsoever, or vice versa? I’m trying to figure out how much deliberation went into picking certain readings, since a language can sometimes evolve more haphazardly and start to sort of contradict with itself. So I’m looking for the various clues that can give me fairly strong indications that two words should be considered facets of the same idea.

If one of the kunyomi readings feels more natural to you than any English ‘key word’, I would actually 100% recommend this. As 訓読み literally means ‘instructional reading’. They are there for the purpose of telling native speakers what the heck something means by itself.

To begin with, Japanese is actually far far far more logical than English, so exceptions to the rule are just that. The norm is what you will come across 90% of the time. I have a (mild) theory that even on-yomi possess some kind of innate meaning, but in the case of the kun-yomi, the meanings are almost always the same at a base level.

The easiest way to identify these things are through okurigana patterns. The kanji only ever means what a combination of its kana means. Any okurigana is not a part of the original meaning, but an extension of it. For example, sooo many verbs finish with the okurigana of める. This is not part of the meaning, but an identifying structure.

For example 決める、温める、暖める、集める、進める、含める、辞める (and many others).

In relation to each verb, める just highlights that something is ‘intensifying’, or 'drawing closer to a ‘full’ state of existence.

決める - To make closer to a conclusion/ decide

温める - To make closer to the state of warmth/ heat

暖める - As above

集める - To make closer to the state of correspondence/ gather

進める - To make closer to the state of progress/ to go on

含める - To make closer to the state of oneness/ to include

辞める - To make closer to the state of stopping/ to resign/quit

All okurigana structures have a ‘base’ meaning like this, which makes identifying them so much easier. However this is a personal theory that people either do or do not agree with, and is still young in terms of research validity.

In conclusion, the okurigana will be your best bet for picking up on the base meanings, while the kana in the kanji itself will give the nuance so to speak, when combined with the imagery of the kanji. This (in my opinion) is why most native speakers usually say 何となく分かる, even if they have never seen a kanji before. They have the intuition for the meanings, they are just not taught it officially.

Oh wow. I was only using okurigana to try to identify whether a verb is transitive or intransitive. Didn’t realize there was another aspect to it, even though it makes total sense in hindsight. How did you come by this? Is it something you started noticing while practicing?

I started noticing it by myself possibly because I forced myself to learn every reading of every kanji I studied, but after noticing it, I did quite a lot of research on the topic. Japanese people themselves (within the linguistic field) are pretty up in the air about whether it is an actual feature of the language or not, but there certainly are books that mention it in terms of ‘tendencies’ that okurigana reveal.

Sorry to revive this thread, but this study method has been living in the back of my head since I read your one-year thread. Been focusing more on grammar lately, but I wanted to start getting my kids into kanji, as we hope to move to Japan in a year or two and we want our kids to be at a similar level to other kids in their grade. My wife and I plan to study the kanji with them, and this seems like a great way to approach it (likely at a slower pace of course). @Asher , you shared your deck in the other thread, but at the time you noted that it was incomplete.

Would you mind sharing your current deck now that you’re further down the road?

Thank you for sharing your method!

No problem at all, I’ll reupload it a bit later today. Basically it is just a extended version of the most popular all-in-one deck on the public anki with a lot of missing kanji/missing readings of kanji that I added over time. I am no expert in setting up the decks, so I’ll also throw in a link to the original deck that you’ll just have to copy the settings of for this one. You’ll also need to download the stroke-order font I believe. Those instructions are also on the original deck page.

Thank you very much, this will be a great resource for us!

Sorry for the late reply here! Here is the deck, plus the original deck with the more comprehensive setup guide.

Original deck-

https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/798002504

My deck -

https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/987959808

Looks like I added about 150 kanji that I came across in the wild that were not in the deck. Really the only difference between my deck and the original is that I always put the most accurate English translation on the top line, filled in the gaps in the various yomikata that were missing, and rearranged the yomikata from most common/least common. I also put some yomikata in brackets if it is a reading of that kanji that is seen in a common word, but not an actual official reading of the kanji. These are few and far between, so it should be pretty obvious when you see them.

I made this deck purely for myself, so I didn’t think too much while editing it apart from consistency. I know that sometimes the linebreak didn’t work correctly when I edited it on ankidroid as opposed to on my PC, so if you see kanji where the first and second English word/translation are on the same line without being separated by a comma, you’ll just have to add a proper linebreak via the PC version.

Any questions or troubles setting it up, just let me know!

Edit- You’ll have to wait 24hrs for the link to my deck to actually work. One of the uploading policies of Anki to check copyright.

Thank you so much for taking the time to upload it!

I have another question. I read the first thread, and this one too, but I don’t remember you discussing it.

How did you grade yourself? Did you require yourself to know ALL the readings AND the stroke order in order to mark yourself right? Just curious, as I recall you saying that you stuck to 3 or 4 new cards a day in order to hover around 70 reviews. Since you spent around 2 hours a day, we will probably go a fourth of that speed and just try to go at a slow-and-steady pace of 1 per day. I know that your personal grading method isn’t law, but it would be helpful to hear about how you thought of things since you have already walked the path.

Additionally, if you marked one wrong and it came up in again review, did you attempt to write it out an additional ten times each time it came up until you successfully wrapped up your reviews?

Doing only one a day, which sounds like a really good pace for your personal goals, I would make an effort to remember basically everything. You will discover yourself pretty quickly how lenient you can be with yourself if you make a really silly mistake that you think you won’t make again. The stroke order itself becomes kind of muscle memory more than anything else, so I would actually be surprised if you forgot that part after a few tries.

A good example of being lenient on yourself is maybe if you are reviewing the card 体 and accidentally say the readings/meaning for 休 instead. Then when you reveal the card you think to yourself ‘oh oops, I just didn’t look at the kanji well enough’. At that point, you have to decide for yourself if you fail the card, or if you actually do know the readings/meanings for 体 but just had a momentary lapse of concentration. I can almost guarantee this exact situation will happen at least a few times, especially on similar kanji, so you have to be your own critic in those cases. For me personally, I fail/pass them depending on if I really do know both kanji and think that getting it wrong may have actually been helpful to not getting it wrong next time. Sometimes making a silly mistake actually increases your memory afterall.

Most of the time if I got something wrong, I wrote it out an additional 10 (give or take) times. Even if you make the odd mistake, if you’re only doing one new card a day, I would be surprised if your total time spent reviewing this way ever went over 30 minutes.

Edit - One small thing. There are a few English meanings, and while you should read them the first time you see a card, I would only ever actively remember the first one. The other words are really only there to help you remember the nuance of the key word.

I think this is really applicable at all SRS.

I apply this sometimes to Bunpro for example.

Maybe is asking for past tense and I answer with the present.

Then depending the result of the question “If I understood that it was asking for the past tense, would I have gotten it right anyway?” I fail the question or not.

I’ve been doing a similar thing since November (when I decided to start learning Japanese, and decided to focus on Kanji a lot because I’m mostly interested in reading Japanese over speaking it). Of course I’m much less advanced, I’m at around 500 kanji right now (+ probably a hundred or so that I can recognize in context but not write or recognize in isolation).

I’m using Wanikani through a third party app that lets me customize the experience but also study on the side with Anki and reading Japanese texts.

Regarding the order of the kanji, I think it only matters very early on, at first even a relatively straightforward kanji like 億 can look scary and I do think that it makes sense to learn 人、立、日 and 心 first but once you have a couple hundred characters under your belt you’ve seen most of the components individually and it’s not too difficult to parse the vast majority of kanji I stumble upon even if I have no idea what they mean.

I definitely think that it’s worth learning to write the kanji. Many resources online (including wanikani) will tell you that it’s probably not very useful nowadays since you’re unlikely to need to handwrite a lot of Japanese, and if you don’t use the skill you’ll eventually forget how to do it. After all, this seems to happen to a lot of Japanese and Chinese people.

This is of course entirely reasonable, but I still think that it’s worth learning to write the kanji even if your objective is mostly to be able to read them. It’s basically the ultimate test of knowledge when it comes to knowing the “shape” of a kanji. If I know how a kanji is written I will basically never confuse it with another. If you know that “to wait” is written 待 then you can’t be confused when you encounter 侍 even if you haven’t learned that (rarer) character yet. If you rely on a fuzzy knowledge about the rough shape of the kanji, it’ll be a lot easier to mix those up IMO. If in a few years I forget how to draw many of the rarer kanji then so be it, by then I’ll hopefully be good enough at Japanese that I will be less likely to mix kanji up in context anyway.

I’ve actually used the Wanikani API to dump practice sheets for this specific purpose: http://e.pc.cd/vGEotalK

I print those, then use a sheet of paper to hide everything but the English meanings. Then I try to draw the kanji and remember the readings. I really find that it helps, if only to identify the kanji that I already know well and can recall with ease and those I need to work on a bit more.

Actually I switched it up: as the number of kanji in my active rotation increases the paper printouts started to become unwieldy. The solution? Anki of course!

Using WaniKani’s API and KanjiVG’s diagrams I generated this deck where basically on one side I have the meaning and cloze-style vocabulary with the kanji blanked out:

And on the other I have the kanji, an animated stroke diagram, the readings and the vocabulary with furigana:

Of course this is mostly only useful as a companion to WaniKani since I use the exact same order. You could rearrange the cards for other methods, I suppose.

I’ve been using it for a week and it’s been pretty enjoyable so far.

I use WK to study kanji and to date I haven’t made any attempt to practice writing. There are two reasons for this: first, because numerous sources say that no one actually writes kanji anymore since everything is computer or phone (even though this is obviously false), and that you’ll just forget how if you’re not doing it a lot, etc. And second, because I’m a lazy, undisciplined student; I want to make a minimal effort and focus on the lowest-hanging fruit, and practicing writing is an added hassle.

But I’ve often thought that I should practice writing, if only to reinforce my memory. See, I can’t even clearly visualize many of the kanji (and I am not a strong visualizer in general, e.g. art). I feel this makes it harder to disambiguate similar kanji - since the different radicals are “meaningless” to me - and I think it also makes it harder to recognize kanji in the wild, since I’ve only memorized their appearance in WK.

Since I’ve also forgotten some kanji I’ve burned, I’ve thought about rolling back to level 1 after I’m done with WK, and doing it over, and practicing writing them this time. But this is probably a lot of wasted effort reviewing kani and vocab I maybe don’t need to review. Speed running through them by N level, or grade level, etc, is probably the smarter move; I shouldn’t need such intense review for most kanji I’ve learned even if I’ve forgotten them, and I can zero in on the leechy ones that way. I’ve already noticed patterns in radical use, meaning, and reading, so I’m not sure that going in grade order will teach me anything I didn’t know, but it probably can’t hurt anyway, and the more ways you can look at a thing you’re learning, the better, usually.

WRT passing items that you “failed” that you actually mostly knew… I do this with WK all the time. I’m actually not concerned with learning the exact nuance and closest equivalent English grammar for every kanji or word; Japanese is such a big elephant that I’m content being in the right general ballpark, and refining my understanding later. Some people feel it’s a burden to “unlearn” things but I’m trying to reach a functional level, where I can parse out some writing and understand it broadly; we are not computers, and trying to learn everything exactly right the first time doesn’t seem like an optimal strategy because we can’t commit it to memory the way computers can, anyway. I do this with Bunpro even more, to the point where I question whether I’m cheating myself - but I see Bunpro as a means to get exposed to a grammar point repeatedly, not as a useful tool for rote memorization (not because it isn’t one; on the contrary, I tend to memorize sentence/answer combos without necessarily being comfortable with the grammar!) Getting stuck on some leech forever because you didn’t get a na or a no or a ni in exactly the right place is miserable and frustrating. My feeling is that I will actually end up learning grammar largely from consuming native Japanese; the point of doing something like Bunpro or any other grammar study is just to get enough familiarity with structures that I can recognize them in the wild and have a good chance of figuring out what’s being expressed.

Keep in mind, the object of language study isn’t really native fluency. I mean, it can be. But unless this is a 100% abstract exercise for you and you don’t care about ever using the language as a language, rough functionality is far more important. Imagine every immigrant you’ve ever met with an imperfect understanding of your local tongue; do they hide away from the world until they’re ready to speak perfectly? Or do they muddle through with terrible accents, limited vocab, and mangled caveman grammar until years of practice and exposure improve them? Which one is more likely to be able to function in an environment where the less familiar language is spoken exclusively, and which one is letting perfect be the enemy of good? Do you think you’re any different? I don’t, and I choose my study methodology accordingly. YMMV, of course.