Hey everyone!

This is the first time I have done one of these posts in a while, but I wanted to tackle one of the highly misunderstood grammar patterns in Japanese. にする、になる、とする、となる.

As always, please keep in mind that this is based off my research, and is open to interpretation.

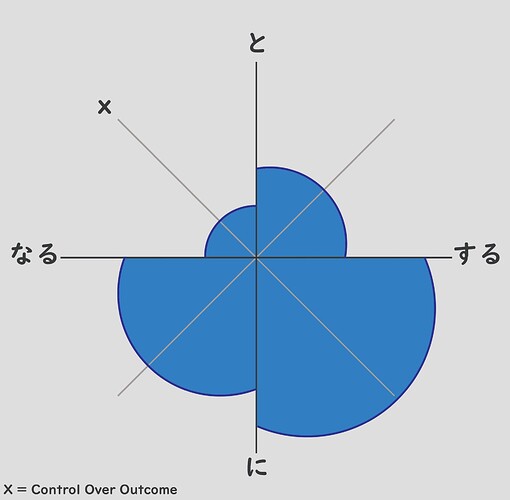

You will find many different translations for these grammar points on many different websites (including Bunpro), but for a moment I would like to present this graph.

Something that should be understood about Japanese before applying many different meanings to many different things, is that the concepts are all the same. Compared to English and almost every other language, Japanese has a very limited supply of sounds/syllable combinations. The result of this is that the language itself has to obey a very strict set of rules for everything to be understandable/distinguishable from eachother.

The very strict set of rules that these grammar patterns adhere to is ‘control’. Control can be thought of in a few different ways, whether it be direct control(する), or just aim/intention(なる).

From the graph, let’s have a look at what some of these grammar points are really saying (in Japanese), and why this results in so many different meanings in English.

Top left -

となる - The lowest level of direct control of the speaker (something became a certain way, and whoever is talking had no say in it). と suggests that an outside factor is the primary controller of the result.

In English this becomes - It happens to be, it has been decided, it has been established, it has become that.

Top right -

とする - With the addition of する, we see that the subject now has a certain degree of control over the outcome, but と still suggests that external factors can (and will) influence the outcome.

In English this becomes - To suppose, to intend, to try, to assume, to feel

Bottom left -

になる - With に being involved, now we see the ability for the speaker/subject to control the situation increase quite a lot. This is because the (external requirement of と) has now been removed.

In English this becomes - To end up being, to reach the point that, to become (something is headed a specific direction, and nothing should stop it getting there).

Bottom right -

にする - Now we have the highest level of control possible. The speaker/subject is aiming toward something, and they have the ability to make that thing a possibilty right now.

In English this becomes - To try to (strong), to make sure that, to decide on, to make someone/something more …

Regardless of what form you see these structures in, they will always have this base meaning that reflects the level of control. Some examples are -

にする、~にする、~ようにする、~ようとする、~となると・~になると、~となっている、~ことになっている、~ことにする、~ことになる、にしては、にしても~にしても、それにしても、にして①、にしてみれば、にして②、として、としても、としては、は別として

Lastly, you may have noticed that I mentioned に being something that the speaker can control by themselves, and と referring to some sort of outside influence being required. Well this is also another common theme that lies in the base meanings of these particles. When you use と, you are usually highlighting an action or state that cannot be completed/cannot exist by itself. に is the opposite of this. に shows that the subject is doing something of their own accord, and that the thing they are doing it to has no say in the matter. That’s why you end up with sentences like this -

姉と話す (talk -with- your sister) (not possible unless she takes part in the conversation as well)

姉に話す (talk -to- your sister) (possible even if your sister doesn’t want to listen)