August 2009, I think. Thats when I went to my first Anime con in Dallas, TX. It was the biggest anime con in Texas at the time, might still be. I deprived myself of sleep the night before, that wasn’t a good idea. It’s never a good idea to deprive yourself of sleep before an event, but I was in my 20s, I thought I could handle it. It was the first time I had been around so many of “my kind”. So many people, so many cosplayers, so many vendors and artists. All things anime, manga, Japan, without actually being in Japan. I figured there would be people there that spoke or at least studied Japanese. I went to a few panels, but one stuck out. It featured a professional manga translator talking about his experience over the past 10 years. It was an interesting panel, a very good and inspiring experience. Talked about some of the issues he came across, the nuances that would rear their ugly head, and how he often had to consult with his native Japanese wife about things….cheater. (jk, Asher) After the panel I remember talking to a girl who also attended the panel and asked if she spoke any Japanese. She said that she did, but she was too shy to use it at the time because she is such a ‘perfectionist’. The thing is, she was speaking English with what I believe was a Russian accent. She certainly had no issues not speaking English perfectly, so not sure what the deal was. Didn’t really matter at the time for me, but I never really forgot that interaction for some reason.

What even is perfectionism? I guess that varies depending on who you ask. All I know is that it has the ability to hamper learning and risk taking. It is a shield that prevents criticism, and can prevent growth. Over the past few years there has been a growing movement among the Japanese learning community that not only is immersion the catalyst the brings forth fluency, but pitch accent too is just as important to sound as “Japanese” as possible. And yes, while the end goal of Japanese for most is speak like a native, or as much as possible, the very notion that something that has to do more with form rather than function being put at the forefront of one’s learning seems a bit absurd.

When visiting the Philippines on a work related trip, I was taken aback by how common English was. It is spoken by the majority of the people there. If you’ve made any customer service related calls in the US over the past few years, there is a good chance that you have spoken to someone from there, even more so than India. If you’ve heard them speak, it’s very clear that they don’t sound British, or American. Does that mean the it ilegitimizes their English, I think not. They are able to transmit information, complete tasks, give instructions, and get paid at the end of the day for it. Some aspects about it may be different, the accents vary, it many not always come off the way you expect it, and you may hear “kindly” quite a bit, but information that needs to be transmitted is transmitted.

While in Tokyo I came across all types of people from many different countries. All with their distinct accents and pitches when speaking Japanese. Yes, there were some people who spoke Japanese very properly and very native like, but they were few and far between. Those that got very good at the language didn’t mind if they sounded like an Englishman speaking Japanese, they were still speaking it and being understood. It didn’t’ stop them from making friends, hanging out, getting things done, or holding down jobs. Each person from each country had their own distinct pitch and accent. Spanish speakers using a softer と in particular stood out to me, along with French people, somehow still sounding like they were speaking French. I lived in a guest house (some people refer to it as a 外人ハウス)and you could clearly hear from the conversations filtering through the paper thin walls who was native and who wasn’t. Did it matter, not really. Those people still held down jobs, went to University and lived their lives as usual in a city as tumultuous and English free (at the time) as Tokyo. Some personalities who promote pitch accent and perfectionism would have you believe that if you don’t sound Japanese, you won’t find success. Judging from the number of foreigners speaking Japanese that is far from perfect on National Japanese TV, I think it’s fair to say that such a claim is total BS.

One might assume that I might be hating on this methodology because perhaps I myself don’t speak it well or don’t sound natural. That is quite the contrary, I’ve always had good pronunciation and have always mimicked spoken Japanese as much as possible. So in a way I was learning pitch accent before I even knew what it was. I didn’t even take into consideration that I was doing so until pitch accent was brought up while in language school in Tokyo. I might have my reservations about other aspects of my Japanese, but how I sound is not one of them. Perhaps a very discriminant pitch accent aficionado may nit-pick, but most people, especially Japanese people are going to care less about how I sound, and more about how functional I am in the language. As Japanese learners, our goals are all different. Some of us may want to sound Japanese which is fine, some people have told me I sound Japanese even if that wasn’t necessarily my priority. For others, how they sound may not be a much of a factor. Others may not want to make mistakes, others thrive on their mistakes to become better. Perfectionism isn’t necessarily a bad thing, I certainly think it’s better than conformity. But I have also seen how it holds people back, and makes them afraid and self conscious. It sometimes keeps them behind textbooks and flashcards longer than they need to be. And in some cases, not speaking Japanese or interacting in Japanese for a very long time, and braking that barrier is extremely important.

It’s kind of crazy, but it has gotten to the point that there are Japanese speaking tier lists for popular Japanese Learning Channel You-tubers. I kind of wonder why, and who really cares? I dunno, you might and if you do I guess that’s cool. Maybe it’s a generational thing that I don’t understand. Back in college there may have been a couple guys who wanted to strut their Japanese skill and be competitive about who knew more, but no one really took those guys seriously. The knowledgable students who were the most sociable and shared knowledge out of good intention were better liked and had better chances of success since their likability transferred to Japanese students as well. We would read, write, and speak in Japanese, but never sat there and deliberated about pitch accent and whose Japanese was better.

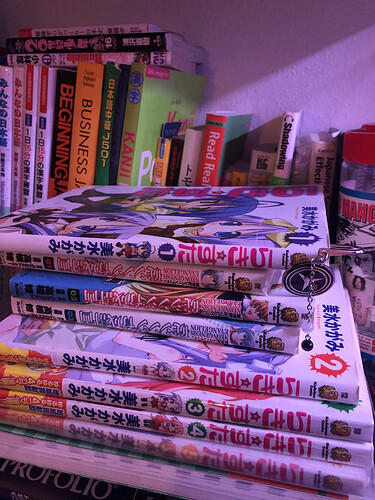

October was an interesting month for immersion. My partner and I have been consistent with Tuesdays which are 日本語の日, where we communicate in Japanese as much as possible. It’s been eye opening in seeing how much she was lacking in her foundation. Despite being almost done with N4 Bunpro vocab, she was still having trouble forming basic sentences with N5 grammar. This mostly comes from still thinking in English when she is forming sentences. A hurdle which haunts many a learner for a long while, spooky. So we’ve been doing some drills and review which reminds me how beneficial it is to teach. You can learn by yourself, but when you have to show somebody else, especially if it’s someone who you generally care about getting better, you do second guess and want to make sure you are providing the right info. Other than that, this month we are trying to do the tadoku contest. For those unfamiliar, it’s where you read as much as you possibly can within a certain time period, be it weeks or up to a month. Word look up is minimal, and you just kind of go with what you know. I’ve decided to try and read through those 5 or volumes of Lucky Star that have been collecting dust for years, and years. Let’s see how this goes.