That is true, heisig did have that intention. But he also tried to point out the inherent meaning within radicals and how to use them to guess the meanings of new kanji. Even radicals that aren’t radicals. For example 漫 the right half of this kanji is not a radical, but heisig teaches it as a ‘heisig radical’, something that can be used to create mnemonics.

However, it should be taught as a radical, because as far as Japanese is concerned, it IS a radical, and it carries a very strong meaning. It means ‘to be billowing/fluid’

漫 - move with billowing form (cartoon, unrestrained)

蔓 - plant with billowing form (a vine)

慢 - mind with billowing form (laziness- the emphasis here is on the inability to focus/still your mind)

鏝 - metal with billowing form (soldering iron)

幔 - fabric with billowing form (curtain)

鰻 - fish with billowing form (eel)

This is just one example. But my point is that there is no point making stories, when understanding the true meaning of Japanese (as its own language, not just as an appendage of Chinese) makes learning kanji so much easier.

As for stretching the theory, this was a long time ago when I understood a lot less about Japanese. I still actually fully believe in this, I just wasn’t able to explain it well at that time because it was still new for me and I hadn’t fully come to any conclusion about my own ideas. To be honest I need to make a video with graphics, because it is hard to explain with words, but simple as heck once you see it.

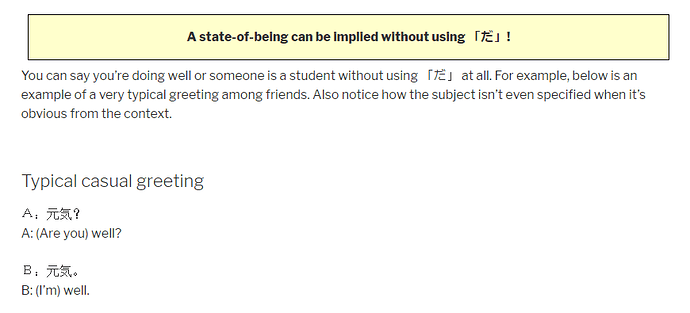

As for this it is a simple omission, the same as any language does in high levels.

Did you know my name is Asher? (Gramatically wrong)

Did you know that my name is Asher? (Gramatically correct but sounds a bit weird to say out loud)

English omits many words, just like Japanese. です is usually omitted because it cannot NOT be there. Everyone knows its there.