Hey guys. This might be a long post, but I’m gonna open with a pretty bold statement.

I think I accidentally unlocked a fact about Japanese that isn’t taught anywhere. Either it was forgotten at some point in history (doubt it), or because Japanese people live inside of it, they think it’s normal and probably don’t even notice it (more likely).

The discovery in question-

Japanese people dont experience space and time in the same way we do. Instead, there are 3 states and one ‘non’ state.

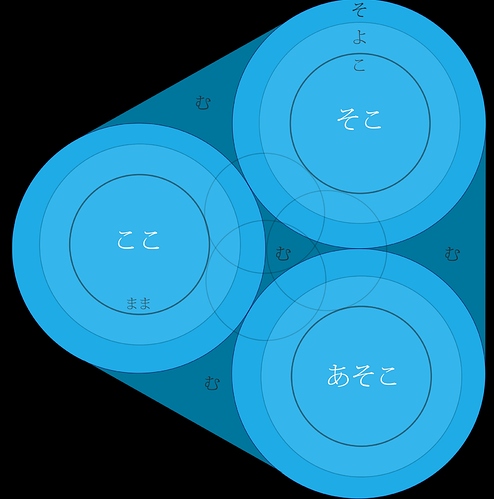

I know this is a pretty outrageous claim. But give me a chance to convince you. I will be happy if you can prove me wrong. On to the convincing, please use the attached diagram I made to illustrate the world. (Everytime you think I am crazy, look at the diagram and really ask yourself)

In Japanese, everything, absolutely everything lives inside まま (yep, just like the grammar point). You have one, I have one, and everything else has one. They are grouped into ここ、そこ、あそこ。If you are the speaker, you are ここ, if you are the listener, you are そこ, if you are something apart from the speaker or the listener, you are あそこ. If you are none of these, you are む (a state of non existance).

Let’s take a look at the simplest elements of japanese first to test this. かな… Yep, here comes part two of my claim. Every single かな has a distinct meaning in relation to まま, dont believe me? Let’s test with a few of the simplest かな, particles.

We think particles have many meanings… Actually, they are 100% consistent. They have only one use, the problem is that when we think in english, we dont have ‘preset’ borders in our heads (the 3 worlds). We have to paint our borders with unique words, japanese does not. Examples as follows.

か- this particle throws a dart in まま, it doesnt ask a question. It presents a real or imaginary event, if that ‘dart’ hits the mark, whoever you are speaking to will confirm that you were right. In this way it looks like a question, but its the same か role in から、かも and every other combination.

に- this particle sets a stage. A stage from where you will describe further. Will you describe something going to it? Away from it?, Its opinion?, That’s up to you, you’re only highlighting it as the stage.

は- This one is great. は points to まま as it should be. Think of は like a flat surface, it just means ‘nothing surprising is happening’ ‘this is the way things are’. You are highlighting to the listener that you are describing your world based on its regular conditions.

が- the opposite to は instead of describing your world based on its regular conditions, you are describing something unexpected or unknown. (A bump on the road). When you talk to someone else, you are adressing their world, so using が to describe ‘normal’ things about yourself is fine, because you are telling someone else things they dont know (bumps).

を- This particle says that whatever is being acted on isnt in charge of that まま.

で- で tells you anything short of the finish line… That’s all. The finish line is what is happening inside まま

と- と adds another まま to yours, it says ‘Ok, if we pull in this outside factor and pretend its part of us from here on out’. Hence why it is exhaustive. It means if in the same way, it pulls in an imaginary or real event and then tells what Its result will be.

も- This particle is a bit like と, but instead of being pulled in, it inserts itself, asserting that it shares a quality with the まま that is being discussed.

Tbh I wrote pretty much every かなs meaning and a few hundred words trying to disprove this but I couldnt. If I just keep typing this will get ridiculous. Instead, if you are skeptical, think of a grammar point and I will tell you how it fits perfectly with only one meaning in this 3 world system. The こ、よ、そ markers on the diagram show levels of conjecture. Imagine the centre of the circle is the person in question, moving further out removes certainty about them. こ turns to よ、ようだ、ような、etc, moving out from there is そ、そうです、そんな etc, even less certainty.

(Need as many people helping as possible).

for grammar/color connotations which would also explain Japan’s fascination with きのこ…not a likely theory either). Otherwise, I agree they appear mnemonic-ish like

for grammar/color connotations which would also explain Japan’s fascination with きのこ…not a likely theory either). Otherwise, I agree they appear mnemonic-ish like