In the ~て (Qualities and States) grammar point, it is noted that the て form can mean more than just “and”. The example used to illustrate this is “このアイスクリームは甘くて美味しい”, which is translated as “This ice cream is delicious because it is sweet”. How can you deduce from this sentence that the ice cream is delicious because it is sweet, instead of just delicious and sweet? I would say that in English these two translations have a significantly different meaning. Is this not the case in Japanese?

Great question. I cannot answer it myself, but I found this: grammar - て used as "because"? - Japanese Language Stack Exchange

I recommend the linked article too.

Also not sure if you know it, but Bunpro has an entry on that too: Verb[て] + B - Japanese Grammar Explained | Bunpro

Thanks for the links. I have not advanced beyond n5, so I had not seen that grammar page yet. From what I understand from the linked article, the meaning is “because” here because the second part of the sentence expresses a subjective opinion. If it were a more measurable adjective like “cheap”, it would have used the “and” meaning. If that is wrong feel free to correct me.

I want to mention a more direct translation of て・で since this has really helped me understand its use.

て・で pretty much means ‘in the manner of’, ‘in the situation of’, ‘by means of’. For example, if we have the sentence お姉ちゃんはつまらない本を読んでいて遊んでくれなかった - broken down we get:

お姉ちゃんは - “As for big sister”

つまらない本を - “(a) boring book”

読んでいる - “Existing in the state of reading”

— 読んでいて - "In the state of [existing in a state of reading]

遊んでくれなかった - “Did not give to (me) in the manner of playing”

Ultimately we get something like “Big sister did not give to me in the manner of playing (when she was) in the state of existing in a state of reading a boring book”.

If we go to natural English, this then could be translated several ways such as: “Big sister didn’t play with me because she was reading a boring book.” or “Big sister was reading a boring book and did not play with me”. You’ll notice that if we use “and”, we don’t really actually change the meaning of the sentence when it had “because” in it because it’s more of an order of sequences - “She was reading a boring book and (therefore) didn’t play with me” carries the same meaning as “Because she was reading a boring book, she did not play with me.”

So in the sentence you provided - このアイスクリームは甘くて美味しい - we get something like “This ice-cream is delicious in the manner of it being sweet” – and in more natural English we can get “This ice-cream is sweet and delicious” – giving the meaning of it’s delicious while being sweet (so then it being sweet has to do with it being delicious otherwise they wouldn’t be put together). The use of “because” in this translation better portrays the “in the manner of” meaning than “and”, but I would still argue that given you look at it the right way “and” can still give off the same meaning here.

You might want to check this post out as well.

Hopefully that somewhat helps.

It isn’t wrong but it may be better to think of て more broadly as a linking particle since it can mean more than just those two.

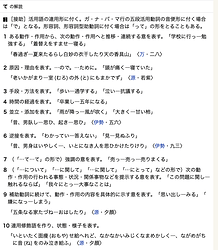

In this screenshot of this page from the free goo dictionary it shows 10 different use cases/defintions

わかっていて 答えない

In this example sentence from no. 6, we would probably translate it as “but”.

An important note is that there is a difference between verbs and adjectives relationship to ~て. In the case of verbs, it is much more likely to have that meaning of ‘because’ or ‘by means of.’ with adjectives it can still have this meaning but the exact example you gave is much more clearly just a linking form of two adjectives a la ~て (Adjectives and Nouns) And… (conjunctive)

I am not sure if this is the original question, but piggybacking off it, my question is not what uses does て have (it has a lot) but rather how does one tell when presented with a sentence, which is being used.

Suppose a native japanese speaker on occasion 1 wanted to say “the ice cream is delicious because it is sweet”. And on occasion 2, wanted to say “the ice cream is delicious and sweet.”

Would this speaker say the same thing on both occasions? If not, what would they say to distinguish the two statements.

— Dave

If you refer to my post above I think this should help answer your question.

In short, て・で carries the literal meaning of “in the manner of”, “in the state of”, “by means of” and in this case, we can translate the sentence as “The ice-cream is delicious in the manner of it being sweet” – both ‘and’ and ‘because’ can replace “in the manner of” to carry the same meaning. However, ‘because’ retains that meaning a lot better than ‘and’ does in this case.

Josh, thanks for the response.

I think that you are saying that the Japanese speaker would say the same thing on both occasions. ね

— Dave

I get that て can have a lot of different meanings. My original question was twofold:

1: Does the て conjunction used here have one “real meaning” which just does not translate one to one to some English concept, or does it have multiple possible meanings from which it can only really mean one thing at a time depending on the context?

2: If the て form really does have multiple possible meanings, how do you differentiate between them in sentences were multiple options give a meaningful but different translation?

After reading the replies and linked articles, my conclusion is that there is no easy answer, but that the intended interpretation is much more likely to be “because” than “and”.

て certainly does have one real meaning that does not really have one English equivalent. This is primarily because Japanese words focus more on ‘function’ than on ‘nuance’ like English words tend to. The ‘function’ that て form focuses on is that (A) comes before (B) in a sequence, that’s all. This ‘coming before’ may be interpreted in many ways in English, but all it really means is (A) happened before, existed before, or lead to (B).

Although this nuance is quite weak and may sometimes need the speaker to clarify the exact meaning, it’s very similar to ‘and’ in English in a sentence like ‘I fell over and hurt my knee’. Everyone listening to the sentence knows that the reason they hurt their knee is ‘because’ they fell over, and that ‘and’ is just showing the sequence of events.

-

It’s both. The “real meaning” that doesn’t have a one to one English concept is that it provides the function of naturally linking the things before and after it. You can loosely consider this to be same as “and”.

It also has multiple possible meanings depending on context. The intention of the screenshot was to show that it has multiple meanings in Japanese to Japanese people. The multiple meanings are not due/related to translation. -

The meaning would be what you would naturally conclude from the context. The lack of clarity could also be considered to be a feature since they are choosing not to be explicit.