So I’ve been exploring my Anki cards and found a lot of goodies. I didn’t realize the extent to which how the word is used affects the structure of Japanese definitions.

Remember when I said:

If it [the word being defined] is a verb, the definition will typically end in a non-nominalized verb, too.

I actually think it’s not “typically,” but always. I have found no exception to this so far. Even if there are exceptions, it’s definitely not a coincidence.

Furthermore, for い-adjectives, most of the definitions I’ve seen so far are copular sentences (ends in である・だ・another い-adjective), which is completely suitable given that い-adjectives are copular in nature.

For words that can be used as na-adjectives, I’m often seeing そのさま, or some other obvious indicator that this word is a descriptor of states of affairs. (Your own question illustrates this - note how そのさま is not used for 例外, which is not a na-adjective, but is used for 凶暴, which is a na-adjective.)

Finally, I did find some examples of words for which all definitions end in a こと nominalizer.

成仏 (N, SURU)

(1)〔仏〕 煩悩(ボンノウ)を解脱(ゲダツ)し,悟りを開いて仏となること。

(2)死んで,この世に執着を残さず仏となること。

(3)死ぬこと。

席替え (N, SURU)

(教室内の)席順を変更すること。

逆転 (N, SURU, No-Adj)

(1)それまでとは逆の向きに回転すること。

(2)事のなりゆきや優劣の関係が今までとは逆になること。

裸 (N, No-Adj)

(1)衣服を着けていないこと。

(2)おおうものがないこと。むきだしの状態。

(3)財産や持ち物が全くないこと。無一物。

(4)隠し事の全くないこと。

抜群 (N, No-Adj, Na-Adj)

This one is interesting, so let me put both J-J dictionary entries.

At first, I only looked at one definition. Here’s the first one:

(1)多くの中でとびぬけて優れている・こと(さま)。

(2)程度のはなはだしい・こと(さま)。

After seeing that, I thought that it abided by my parameters, but then I looked at another dictionary. Here’s the second one:

(1) 多くの中で、特にすぐれていること。ぬきんでていること。また、そのさま。

(2) 程度が大きいこと。また、そのさま。

This is just like your word, 凶暴. They are both ことs and さまs. But 凶暴 is not a no-Adj, unlike 抜群 (this word). So I don’t think the monolingual dictionaries implicitly indicate whether something is a No-Adjective just by how they define it. Oh well…

These are all nouns. They are not also na-adjectives unless the entry clearly signals it (e.g.: by using さま as in 抜群 or 凶暴).

I’m not sure if there is anything else connecting these words. For instance, not all of them can take する, but if they can’t, then they can be used as の-adjectives. But this much might just be a coincidence due to a limited sample.

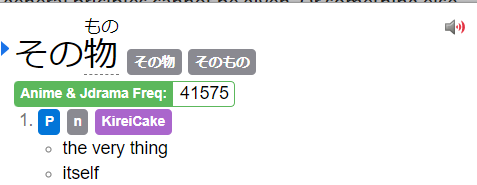

All in all, all I know with reasonable certainty is that if the definition ends in the こと nominalizer, then the word is a noun. So I think you are right, @josh, that the そのもの is doing more than just indicating that it is a noun (because we would have already known that for 例外 from the first sentence where it ends in こと).

From now on, pay attention to the form of the entry: it will vary based on whether it’s defining a verb, adverb, noun, na-adjective, some combination of the former two, i-adjective, but there is a system behind it all.