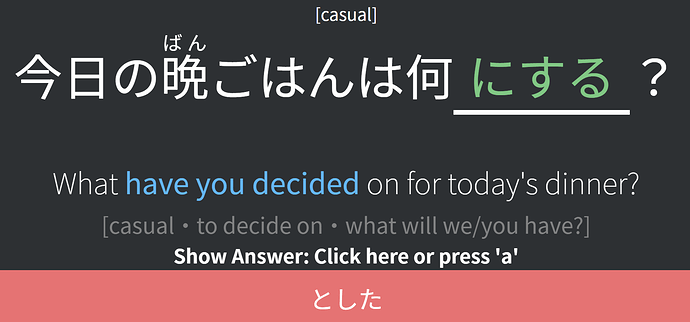

Why is this にする and not にした or にしている? The Japanese means “What will you decide on for today’s dinner?”, doesn’t it?

Not quite. It’s not a literal translation - it’s more akin to “what will you have for dinnner”, it’s just that にする has a focus on having made a decision rather than a focus on the actual action that will be taking place (having something for dinner, in this case) - hence the translation of “to decide on” for にする.

The reason it’s in the non-past tense is the actual thing you have decided on is in the future. にした would only be appropriate if you’re talking about it after having already had dinner, but I’m not sure if something like 昨日の晩ごはんは何にした would be natural to ask and couldn’t quickly find anything to tell me if you can use the past tense in this construction.

にする is a present and future tense, so the sentence does translate fairly to “What will you decide/choose for dinner.” If you want to be super direct, I’d translate it along the lines of “As for the topic of today’s dinner, what will you make it (what will you turn it into).” にした would be used if you’ve already decided or if you’re asking if they have already decided. にしている is the continuous form, meaning that you’ve started thinking and are still currently thinking of what to decide on, that’s what I’d argue anyways.

That’s what the English translation says. “What have you decided on for today’s dinner?” That’s past tense, isn’t it?

Literally, I think @chroipahtz raises a valid point on the English being offered here.

And also:

Yes, you can see some of the nuance here. I will say that I hear this phrase a lot in Japan and it’s meanings vary from:

What will you have for dinner?

What are you thinking about for dinner?

What have you decided on for dinner? (the nuance is the implication that the other person may have considered this already)

And so as not to assume anything about the other person, the translation kind of means all three of these at once (I don’t claim that this is the case every time because language is quite fluid).

Ya I have an issue with that a lot too. I don’t know if I am bad at telling sense which would be weird and I am pretty sure isn’t the case. A lot of questions to me seem like the english translation kind of points towards a tense that the question isn’t looking for. I always kind of wished they had an option to show the tense kind of a sentence. Simular to how they have a toggle for hints. But I don’t fuss to much over it I kinda just got used to it. So long as I understand I just redo and change the tense

In English, “have” + past participle = Present Perfect tense. (The verb “have” is present! Otherwise it’d be “had”.) It means you’re in the CURRENT state of having done something.

But again, isn’t that what している is for? Or even してある?

にする - will decide on

にしている - am deciding on

にしてある - have decided on

Sorry to belabor this point, but I really want to understand the nuance and how it translates to English as well. There is also the possibility that you would just use a specific transitive verb “to decide” (that I don’t know) instead, right? And the possibility that casual speech ignores this nuance in favor of being idiomatic.

Edit: Thinking literally, if する means to do or to make, and に represents the destination (including conceptually), then that would seem to back up what I just said, wouldn’t it?

You’re not entirely wrong, but I’m afraid this is inherent in translations. Things aren’t always going to have the same tense, or even the same grammatical function.

So yes, while from an English standpoint it makes sense that にする = “will decide on” and にしている = “am deciding on”, just going from what the phrase にする means in Japanese this is not the case. And describing why in English is going to be very hard, because at some level it’s going to boil down to “that just the way it is”. English is not Japanese, and Japanese is not English, and the exact same thing is sometimes expressed in wildly different ways, grammar included.

No, because にする in a literal sense has nothing to do with the act of making the decision. にする is not about still needing to make the decision, it’s about still needing to have dinner (presumably - the speaker is not always aware of when things happened, of course). The act of making a decision is implicit in this phrase, not explicit, so when the decision is actually made is irrelevant to the tense of にする, にする refers to the actual thing you have decided (or will decide, or are currently deciding) to do. Like @conceptualshark mentioned, in terms of the decision being made, it can have any of these tenses, or all of them at once

Technically, yes. That’d be 決める. The difference there is that 決める does refer to decision-making explicitly and literally, rather than implicitly through nuance.

Whether 決める is natural to use, however, is another matter. But technically speaking, yes, you could absolutely say something like 今日の晩ごはんは何を決めたか

On a more general note, at the risk of being wildly unhelpful, there’s a point where translations fall short inherently, and I think you’ve hit it. Trying to equate Japanese grammar to English grammar is going to confuse you to high heavens - as is just trying to equate Japanese to English on any level. Intuitively it makes sense to want to equate things directly, but for idioms it’s a bit like asking where the animals are in the Dutch version of “it’s raining cats and dogs” (which literally translates to “it’s raining pipe stems”).

Nice explanation, I think this cleared it up for me. Ultimately I didn’t realize that にする was idiomatic, so I was still looking for patterns with it. I think Bunpro could benefit from some text saying “this is an idiom, just accept it” in cases like this. Thanks again.

Yeah. They really shouldn’t say that にする= “to decide on”. But to be fair, the grammar point in Bunpro does include this:

“In this example, although the common translation is ‘to decide’, it is actually much closer to the slang expression ‘to do (A)’ in English. This means that the literal translation is actually ‘I’ll do a beer’, or ‘I’ll make it a beer’.”

In this case, you could think if it as, “What will you do for today’s dinner?”, though that really matches “今日の晩ご飯は何をする。” better, and does not account for the に.

To be more literal about it, recognize that に simply marks what precedes it as a target. So, 何にする is asking what you aim to do. “As for today’s dinner, at what will you (aim to) do?”.

Once you recognize that に is marking a target, there’s really no need to treat にする as a separate grammar point. It is just adding に to する. Frankly, most Japanese grammar points are like that. That’s why Cure Dolly’s videos on YouTube should be mandatory viewing for Japanese beginners. She does the best job of clarifying the actual structure of Japanese, so you can break a sentence down and have it make sense, rather than memorizing a bunch of rules and rule exceptions which don’t actually exist in Japanese.

I didn’t intend to rant on like this. Apologies.