Hello! As this thread goes on I will probably post about various different kanji and thought it’d be a good idea to introduce some terminology bit by bit so that future discussions make sense. So, first topic of discussion to that end is…

The Six Varieties of Kanji (六書)

In Japan, one common method for classifying kanji is by splitting them into six different types. This system is based on historical classifications and is still used in modern native kanji dictionaries. You may be sort of familiar with some of these categories or intuited some of them. Let’s get into it.

Type One: 象形 (しょうけい)・Representative Pictures

This type is literally just a picture of the thing, so like how 木 is literally an image of a tree and 人 is literally an image of a person (although harder to see that now).

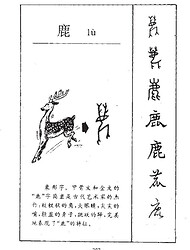

Most learners first learn about this sort of kanji and understand kanji in these terms and is probably the easiest type to learn, assuming you know the actual origin of the image. There are a lot which in modern writing do not really look like the thing that they are, which may lead learners and natives alike to not realise what they are looking at is a literal representation. E.g., 鹿 was an image of a deer. The below image is Chinese but you can see the evolution on the right:

This type is also sometimes referred to as pictographs.

Type Two: 指事 (しじ)・Abstract Representation

This type is an image that represents a more abstract idea. Easy examples include 一、二、三 (one line is “one”, two lines is “two”, three lines is “three”), and things like 上 and 下.

指事文字 are not very common and generally easy to understand. There are sometimes 指事文字 where the meaning/use has changed which could cause confusion but generally these ones are simple to learn and understand.

This type is sometimes referred to as logograms.

Type Three: 会意 (かいい)・Combined Ideas

This type is a combination of simpler parts which represent things or ideas and create a new meaning when put together. This type is highly suited for using mnemonics as the story used will literally be the true origin of the kanji. Common examples are 森 (three trees make a forest), 休 (as person 亻resting on a tree is having a rest), 炎 (fire + fire = FIRE), etc.

A lot of learners mistakenly believe that most kanji fit this pattern when they start learning as a side-effect of using mnemonics, which encourages assigning meaning to all kanji components when they aren’t necessarily being used meaningfully in that specific kanji (which we will get to in the next type).

This type can be called compound ideographs in English.

Type Four: 形声 (けいせい)・Meaning and Sound

This is by far the most common type of kanji and therefore the most important one for learners to understand the workings of. This type of kanji is made up of a ‘semantic component’ (意符) that shows the meaning and a ‘phonetic component’ (音符) that shows the pronunciation. For example, 時 is made up of 日, representing time, and 寺, representing the pronunciation じ. Sound components can then be used to guess the readings of various other kanji. From 寺 (じ) we have 時、持、侍. But we also have exceptions like 詩 (し) and 特 (とく). Most sound components are inconsistent like this.

An important thing to note about this type of kanji is made up of two parts (there can be complications but just keeping it simple here). This means that when using mnemonic systems meant for learners it is artificial to split this type of kanji into more parts. For example, if we have something like 時 then it is possible to split it into three: 日、土、寸. Doing this is of course fine for memorising but it does have the negative that it makes it harder to intuit the actual makeup of the kanji.

Another thing to mention is that the phonetic component will only ever be related to the on’yomi, as it is based on the usage in Chinese. The kun’yomi will never be hinted at by the sound component.

One more thing to note is that the semantic component will normally also be the “radical”, which is the component used for dictionary classification. I will probably write something about “radicals” in the future as the terms are used in various different ways in English which can make it confusing.

This type of kanji makes up the vast majority of kanji so recognising it and understanding what it is will help you analyse new kanji you come across and guess the meaning and reading in many many cases. It is really a super power.

Type Five and Six

These types are actually about kanji usage more than formation so I will leave them out for now and talk about them another time. Something to look forward to

So, let’s apply this. Let’s say I want to introduce the kanji 取.

We can see that it is made up of 耳 (which is an image of an ear, 象形) and 又 (which is an image of a hand, 象形).

This kanji, 取, represents a hand ‘taking’ an ear. This actually comes from the practice of soldiers cutting the ears off of dead enemies (to count them). So 取 is actually 会意文字 (combined ideas character).

What do you think? Does this sort of classification help or make things more confusing? If you already knew about this sort of thing, how or when did you learn about it? Do you wish someone told you on day one of learning? Do you make use of this sort of system when learning or just ignore it?

)

)

The more stupid the association, the better (お皿.

The more stupid the association, the better (お皿.  …)

…)