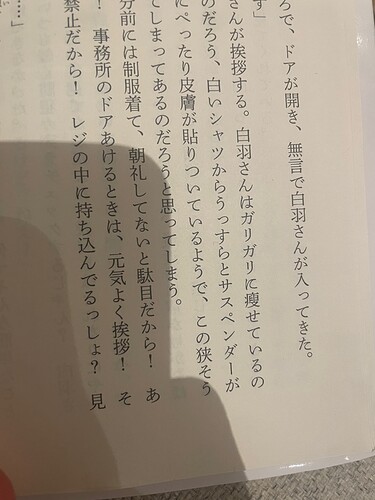

Bit of a random question, but in コンビニ人間 I was a bit stumped by the character 瘦 for a while.

Eventually I realised it is an older version of 痩せる.

In Jisho.org at least it mentions ‘Out-dated kanji or kanji usage’.

I wondered whether this is a accident/has no particular nuance, or whether there is some nuance 瘦せる adds.