I often try to read the example sentences on bunpro within grammar points or reviews and ask myself “If I was to make this sentence myself in Japanese how would I go about it” as a test for myself to compare it to the actual Japanese sentence written on here, and I feel it usually helps me learn where I am messing up.

I came across this sentence この店は美味しいということをよく聞きます - “I often hear that this restaurant is delicious”.

When I read the English and did my make believe test in my head I wanted to say it as この店は美味しいのはよく聞きます。

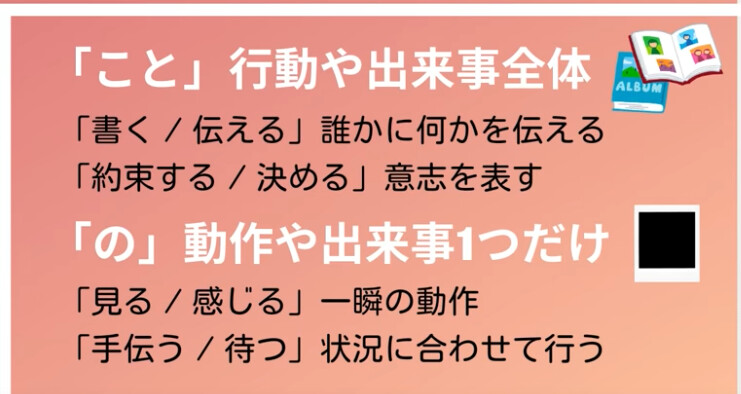

Am I wrong to rephrase it like that compared to the original on here? And if so what would you say the reason is? I have done a bit of looking into it and it seems の vs こと is a pretty discussed topic, but a lot of the time is just sort of a kick the can down the road sort of problem and learners are told to come back to it later or learn from experience. I would be interested in any tips or viewpoints you all have on the differences between them and when each are more natural than the other.