If we put the verb in brackets, your sentences look like this:

- 田中さんが勉強を [します]

- 田中さんが [勉強します]

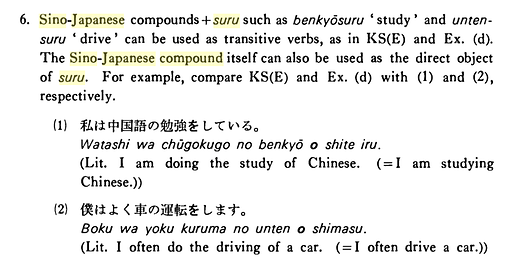

In the first sentence, 勉強 is the noun that 田中さん will する.

In the second sentence, 勉強する is the verb that 田中さん will do.

As @s1212z pointed out, する is Japanese’s quintessential transitive verb (conversely, ある is Japanese’s quintessential intransitive verb). In Japanese, the distinction between which verbs are transitive/intransitive is:

- Transitive verbs: Receive the を particle

- Intransitive verbs: Cannot receive the を particle*

Let’s look at the second sentence again:

We have no を in this sentence, which means that what 田中さん will 勉強する is omitted either because it is implied, or because it is unimportant. Anyway, to add what 田中さん is studying in both sentences, we could say:

- 田中さんが [英語(の)] 勉強をします

- 田中さんが [英語を] 勉強します

You’ll notice that both sentences only have one を per verb.

So really, there’s not a whole lot of difference in meaning. But, you can think of [Noun]する as a means of “verbifying” the noun whenever there’s no を directly before する.

* The only “exception” I’m aware of is movement verbs (like 歩く、走る、飛ぶ), which can be used with を. This simply causes the verbs to behave transitively though, which can also happen in English: “Sail” is generally not a transitive verb, but it is still possible to say something like “sail the seven seas” and use it transitively. (“I ran the marathon” is another example of a transitive application of a movement verb.)

) between textbook “written” and general “spoken” at one point or another.

) between textbook “written” and general “spoken” at one point or another.