Hello,

I’m a little confused about ご/お~いたす’s explanation,

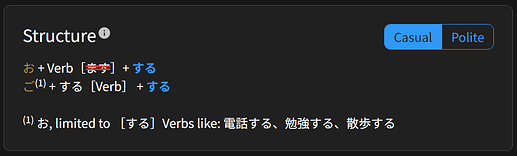

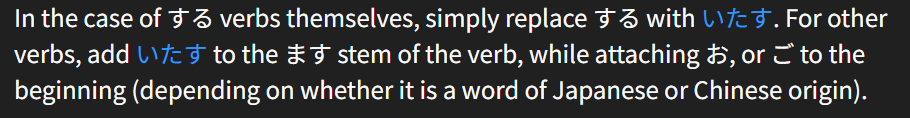

Apparently, the usual would be お but sometimes it’s ご (and sometimes nothing). However, I don’t really understand what prompts one or the other for the the する verb, in the explanation it loosely say it’s お if it’s japanese origin and ご if it’s chinese origin.

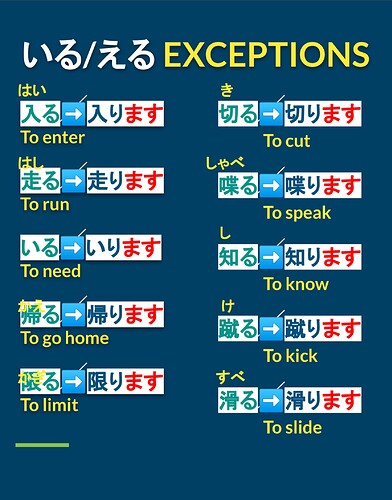

Maybe it’s obvious and I never got it but how do I detect that? I think I’ve heard somewhere that all [Verb]+する were of chinese origin as in “we put a hanzi word and added する to it and boom, verb time” but there’s exception to that? Do I have to learn in a case-by-case basis or there’s little trick to find it?

I also actually don’t think I fully understand what the little (1) means, is it お電話いたします? That’s the exception? Or it’s the opposite and it should be ご電話いたします.

Probably easier than I think but I cannot wrap my head around it to correctly integrate that tid-bit.

Thanks in advance.