(Im german, so sorry if my english isnt perfect.)

Thing is, most things are explained in a very western-oriented way. It takes alot of english words to define a relatively simple japanese concept.

Because I feel motivated I will share something I noticed a while ago:

Japanese works alot with modifiers. Like alot alot. To form a sentence, usually that which precedes a word modifies that which follows it; In a (A)(B) scenario, usually (A) modifies (B). It is almost never the case that (B) directly modifies (A).

Example: in:

ある女の子が先輩のアパートで行われた飲み会に参加した日 (…)

The entirety of ある女の子が先輩のアパートで行われた飲み会に参加した ends up modifying/saying more about 日.

It made me wonder, why then do we call particles markers?

Why not just use this same principle on them?

I.e ドレスを: を should not be seen as the thing that modifies ドレス as an object, but rather:

を is the concept of an object as a “thing/symbol”, and ドレス modifies that objectified “thing/symbol” as a dress.

Any type of word+particle is seen as a single unit, where (A) modifes (B) and both are linked to eachother.

That is also why in speech, particles are often pronounced as part of the word attached to it. (example:ドレスを often sounds like ドレソ.)

Basicially, particles as not simply grammatical connectors, but as integral parts of a conceptual framework in which the whole unit—(word + particle)—takes on a specific functional meaning,

with the word modifying the broader concept introduced by the particle. It’s almost like the particle acts as a container for the meaning, and the word fills it with specific detail or identity.

So in the case of ドレスを, i am arguing that the particle を isn’t “assigning” ドレス as the object in a conventional sense,

but rather establishing the abstract notion of “object-ness,” which ドレス specifies by identifying what that object-ness refers to: a dress.

This also corresponds to the “stage-like” nature in how japanese grammar works, and how any sentence seems to be building up to a conclusion.

We are introducing these concepts, going through stages of conceptual grammatical/logical structures and asigning them a new meaning each time.

allow me to explain: On a stage, we have our concepts, which are always the same. It is the rough outline of a theater. Now we introduce the things inside the theater.

“As protagonist we have today: Paul!” in japanese: “As object we have today: a Dress!”

Meaning particles embody abstract frameworks and words provide the content.

The engines act like a button; We have prepared our roles, now we need to make them play.

How do we make them play? By either assigning action (Verb), existence (Copula) or attribute (Adjective).

This same modifier-modifiee rule also applies to those engines of course:

ドレスだ would therefore not correspond to saying “a dress as existing”, but rather, we define existence as a dress.

This is also why the endings of these engines are always the same. (verb => always ending with う, Copula => Always だ (Of course including Forms of だ), Adjective => Always い or な / Also copulae in a way)

Because these are the frameworks; The kanji preceding them are simply defining the framework as something more specific.

In a more philosophical way, this somewhat represents Japanese focus on order, harmony and logic, where each aspect has a specific role to play, and that role is center-stage. It aligns well with the idea that Japanese grammar isn’t just about assigning grammatical roles but about progressively establishing contexts where meaning emerges in structured layers. This might also explain why Japanese allows for so much implied information—once the framework is established, additional details can be left out because the conceptual space has already been defined.

You dont have to literally embody this logic while translating and can still see particles as markers, of course.

It just helps to see it through this lense, because it will open up the backwards-thinking of the japanese language.

Literally, often reading japanese sentences backwards is easier. And this is one of the reasons.

What is intrinsicly a “marker” for us westeners, is in actuality a “markee” (the opposite) in japanese grammar.

But by seing it through this lense, all of a sudden, you dont have to translate backwards anymore;

Backwards:

ドレスを着る

3. 着る (Wear)

4. を (a (somewhat implied in を))

5. ドレス (dress)

Frontwards:

ドレスを着る

1. ドレス specifies the following framework as “a dress.”

2. を introduces the framework of “object-ness.”

着る (to wear) activates the framework, assigning an action to the concept.

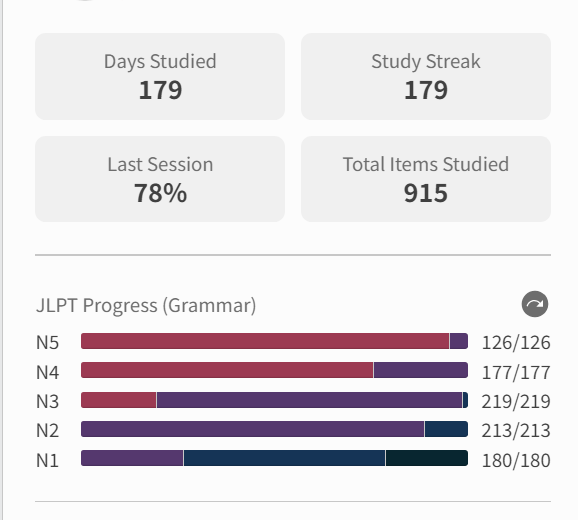

Note that I have been studying japanese for only around 200 days alongside a ton of normal schoolwork, so im nowhere near perfect and this is just casual observation. Only languages I can really understand are Latin, German and English-- but I have noticed some similarities between German and Japanese in particular.

(Mostly that both languages are very flexible-- and beautiful  )

)

)

)