Welcome to the first day of GrammarInTheWild!

Feel free to take a stab at translating the sentence.

If you are up for a challenge, try using the grammar in a sentence of your own!

We will post a follow up version with our own translation with tomorrow’s GrammarInTheWild.

August 21th

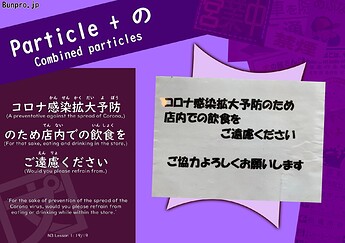

の

Past Grammar

August 20th

August 19th

Translation

Notes :

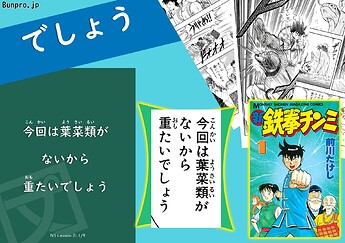

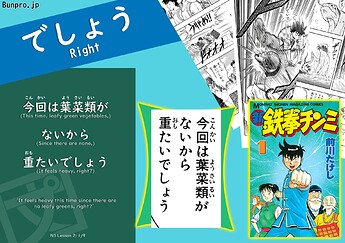

An interesting point to note here is 重たい! This is an interesting adjective that doesn’t have a 1/1 translation in English, and describes the ‘feeling’ of weight, rather than the actual weight itself. A perfect example of this is a sandbag! A sandbag may only be 20 kilos, but because the weight shifts all over the place and isn’t ‘firm’, it usually feels much heavier. 重たい is used to describe things like this that ‘feel’ like they have more weight than they really do.

August 18th

Translation

Notes :

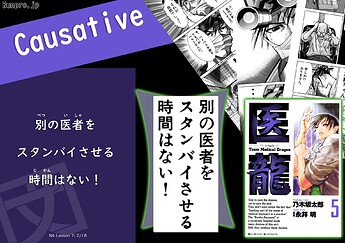

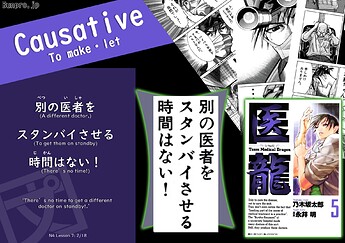

And the difference between 別 and 他 is…? In the beginning, sometimes these two can be hard to differentiate, but there is actually a pretty big difference. 別 usually strongly focuses on eliminating the first option, so something like 別の仕事を探したい would usually sound like (I don’t enjoy this job, I want to quit it and find another), whereas 他の仕事を探したい would be taken more as (I want a different/another job -possibly in addition to this job-). So be careful when using 別 unless you are trying to create space between the thing you’re talking about. In this example, they want a different doctor because the one they currently have is reckless and a bit of a maverick.

Side-note - I strongly recommend this manga to anyone that is reasonably confident in their kanji. It has almost no furigana except for names, and includes a * next to any medical word it introduces, with a note in the margin about what it means.

August 17th

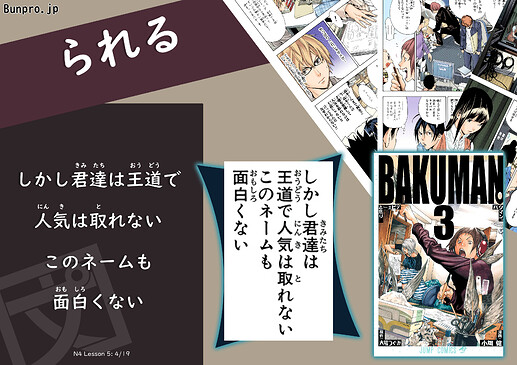

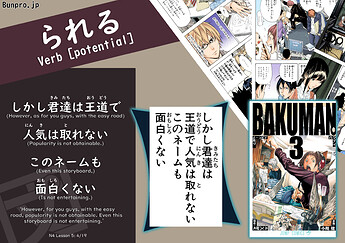

Verb[Passive]]](Verb[passive] | Japanese Grammar SRS)

August 16th

Translation

Notes

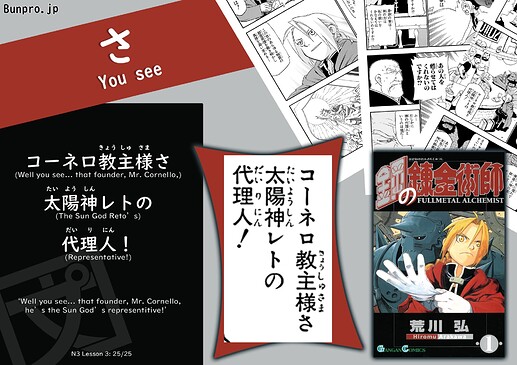

Although there were some comments mentioning that this could be several different meanings of さ, this might be a good time to reiterate it, to help point out a common feature of manga. Extremely often, to save on space in panels, a 句点(くてん) 。(full stop) will be omitted, opting for a new line of text instead. If sentences ‘seem’ to stop, but there is no full stop at the end of the line, you can usually safely assume that the author just didn’t include a full stop.

August 15th

Translation

Notes :

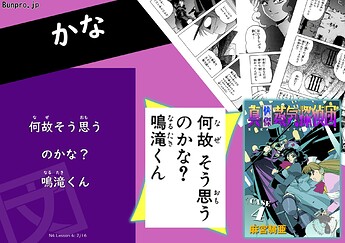

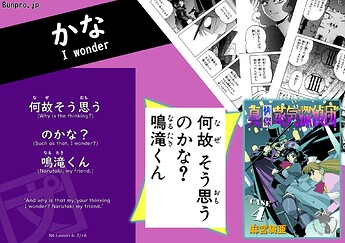

This sentence is one of the first ‘true’ examples we have had in GrammarInTheWild, where it is not possible to tell who the sentence is directed at purely from what is given. It could be ‘He/She/They/You/I’, and further context is needed. In these cases, it is (usually) better to translate it to ‘that’ being the subejct. ‘That’ being anything that is less important than the actual question itself. ‘Why is -that- the thinking?’

August 14th

Translation

Notes :

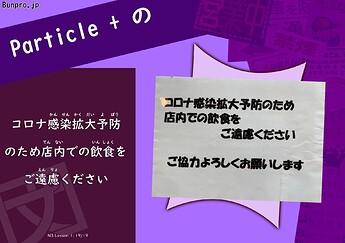

From the ‘strange translation’ here (at least following the initial sentence), I wanted to highlight the overabundance of nouns/noun like phrases in Japanese. In English, we tend not to focus as strongly on which part of the sentence has the most weight (as far as word type is concerned), but in Japanese, most words being nouns allows for a lot of predictability with the type of particle you should use, and what the overall nuance is.

Everyone did a really good job with this translation!

August 13th

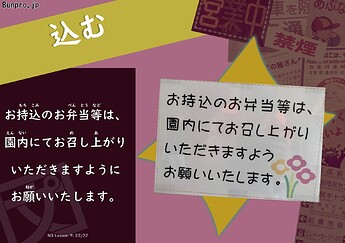

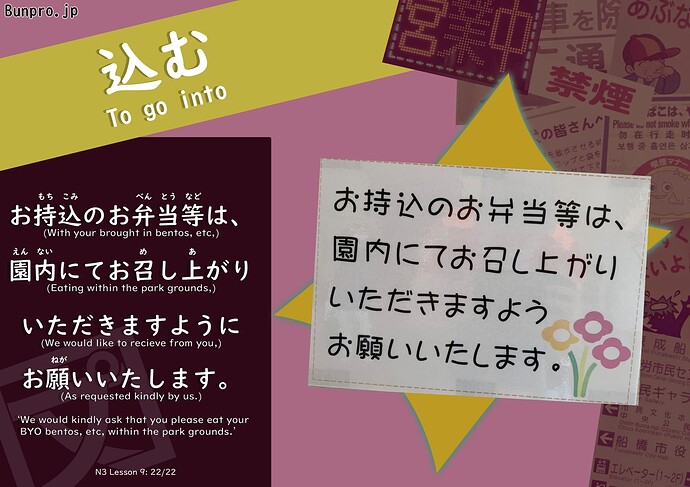

Translation

Notes :

When sentences have an immense amount of polite language like this, it can actually be easier to work from the end, to the start. よう(に)お願いいたします (to respectfully petition/request), いただきます (the reception of), お召し上がり (humbly eating a meal). Final note 〜ますように usually means that you want something to happen for the person you are speaking to’s sake, not your own.

August 12th

August 11th

It will be street signs after this for a few days, to take a break from manga!

Translation

Notes:

The rudeness associated with ~てやる does not come from it implicitly being rude, but from the extreme closeness that it conveys. Using this phrase with someone that you do not already have a very well established relationship with (same level) can result in perceived rudeness or lack of respect. In English this is similar to ‘to get fresh’ with someone, or to just overconfidently assume that you are on equal footing with them/above them.

August 10th

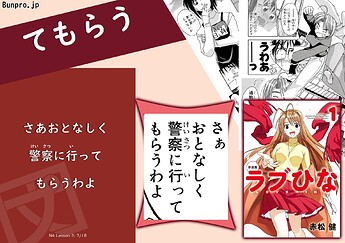

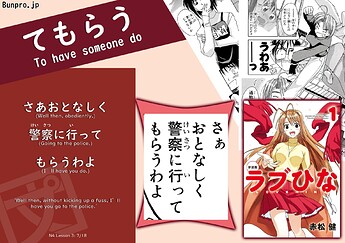

Translation

Notes :

おとなしい and おとなしく generally have a slightly different nuance. The adjective form often does mean ‘obediently’, or even ‘docile’. However, when it is used as an adverb, it can mean to do something without ‘causing a fuss/kicking up a stink’. This is especially true when directed at another person.

August 9th

Translation

Notes:

This panel uses one of the rarer, (but still common in storytelling) functions of その. Here, we see その highlighting the entire first clause as the ‘body’ of the following noun. So 行為 (deed) becomes ‘Toward that deed of (having attempted to steal away the sacred land)’, where the deed itself is everything in the brackets.

August 8th

Translation

Notes :

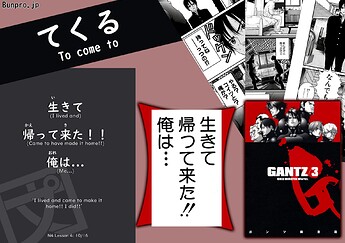

An interesting part of this excerpt is the ‘は’. Although the sentence finishes abruptly, apart from assuming that 俺は is connected to the first sentence (which would be natural), it would also be natural to assume that they were about to say something about an ongoing state, like 「本当に生きている」. In this case it would just imply the persons shock about the ongoing state.

August 7th

Translation

Notes :

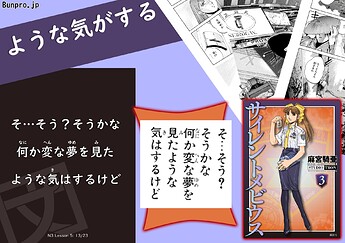

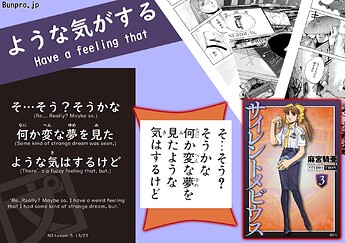

While the usual grammar construction here includes が, the addition of は instead has a few subtle, but important functions. Firstly, it could indicate that this dream/feeling is a repeating event, and therefore not surprising for the speaker. It could also indicate that it felt so real that they don’t know whether to classify it as a dream or not. Lastly, it could also mean that she has told the person that she is speaking to about that dream/feeling several times, changing it from が, to ‘this ‘regular occurance’ dream/feeling’ は.

August 6th

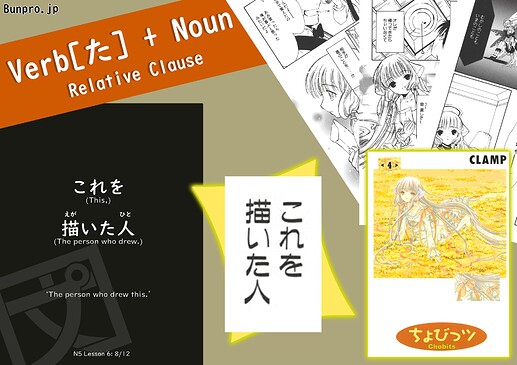

Translation

Notes:

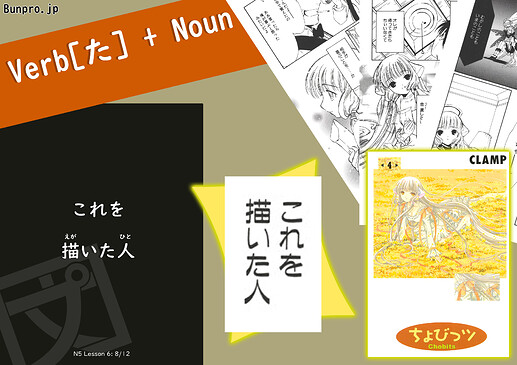

Good work with this one! For the people that didn’t quite get it on the mark, remember that in Japanese everything before a noun in a clause will usually describe that noun. In this sentence the noun is 人, so これを描いた (drew this) describes 人. Becoming (The person -人- who drew -描いた- this -これを-)

August 5th

August 4th

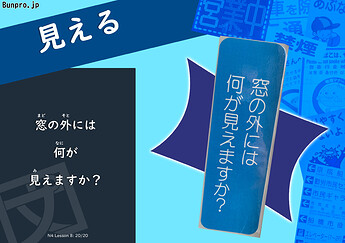

Translation

Notes: While 見える used to be a conjugation of 見る, it has come to be used as it’s own stand alone word these days with it’s own conjugations. As it is referring to the thing itself, and not the speakers ability to see that thing, it is closest to ‘to be visible’ in English. Hence why this verb is regularly used for things that are visible, regardless of whether you are looking at them or not. 見える is only rarely used when ‘searching’, or some special ability is required to ‘see’ the object.

August 3rd

Translation

Notes: While 投石 is just a ‘thrown rock’, remember that most of the time there is no indicator of plural in Japanese. In these cases, it is usually up to context to tell. In this panel there was a very large amount of rocks thrown, but the author chose not to include any indicator of number (such as たくさん). This is probably because they wanted to highlight the confusion of the person who shouted this sentence.

August 2nd

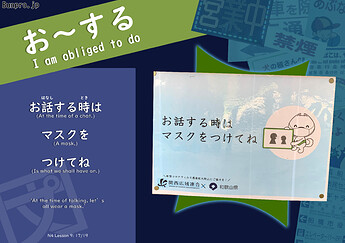

Translation

Notes: When there is a verb of obligation ‘the speaker will ‘humbly’ do something’, paired with ~てね, which sounds like a request, what happens? It transforms into something similar to ましょう! While the speaker is saying that ‘Respectfully, while speaking, a mask will be worn’. This ends up sounding a bit like (Because I will do (A) out of respect for you, please also do (A) out of respect for me).

August 1st

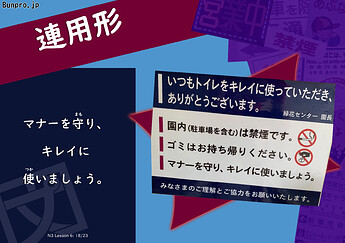

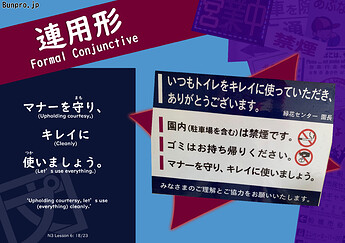

Translation

Notes:

In a sentence sign like this, it is really up to the interpretation of the reader exactly what should be キレイに使いましょう (used cleanly). As all of the points in the sign refer to the park, the most natural assumption would be ‘the park, and all of it’s facilities’. Or simply ‘everything’. It may also be worth noting that マナー in Japanese, doesn’t quite have the same nuance as in English. マナー refers to being aware of your surroundings, and acting accordingly. This is much closer to ‘etiquette’.

July

July 31st

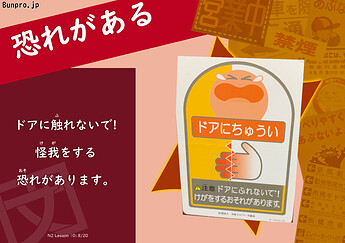

Translation

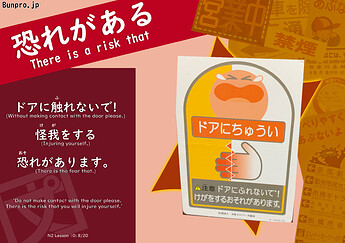

Notes: ドアに…?えっ?…に? It looks like you guys noticed that に seems to be used is a little bit of an unusual way here. This comes from the difference between 触る(さわる)、and 触れる(ふれる)。さわる tends to focus more on ‘touching’, in the general sense we think of it in English, while ふれる is more like ‘come into contact’. に触れる/触れない is an example of omission, in which the を is actually placed on the part of the body that is being made contact with. 手をドアに触れないで! When the body part is omitted, it is usually because it is obvious (picture of the hand on this sign), or because it means ‘anything’, ‘don’t contact the door with -any part of- your body’.

July 30th

Translation

Notes: Good translations yesterday! While ましょう does not always mean let’s as in ‘both of us right now’, it does usually mean let’s as in ''This is generally something that would apply to anyone". This ‘let’s’ is also used quite often in English this way, like a parent saying ‘let’s remember to look both ways before crossing the street!’. What the really mean is ‘everyone should’.

July 29th

Translation

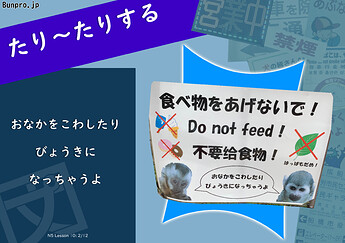

Notes: When たり is used in sentences like this, it can be a bit confusing at first. In English, the ‘single’ たり has a similar nuance to ‘ohhh (verb) ya know?’. This probably sounds a bit odd, so let’s look at an example. Let’s pretend you go to a friends house, and you say ‘So what are you up to today?’. Their reply is ‘Ohh… Chillin, ya know!?’. Here it just shows that ‘while -chilling- is something they are doing, it is not strictly the only thing’. It is important to differentiate this from ‘and stuff/and things’, because these translations always imply that there ‘are’ other things. たり ‘may or may not’ have other things, similar to ‘ohh…ya know?!’.

July 28th

July 27th

July 26th

Translation

Notes: This is another example of a sentence finishing on a particle, instead of the verb. Although we mentioned last time that the verb will usually be いる, or ある in these cases, many other verbs are also possible when the context is clear. Some examples are 来る、行く、言う、やる、する、通う、住む、食べる、and almost anything that would be considered ‘easy’ to guess by the listener in a particular situation.

July 25th

July 24th

Translation

Notes:

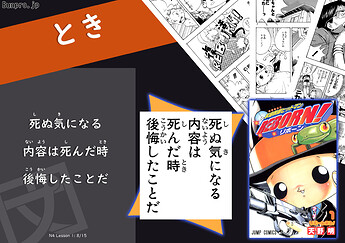

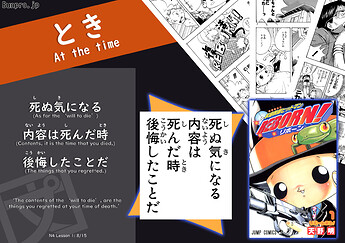

For a sentence like this, it can be confusing even when there is context! Something helpful to do is split it up into logical segments. The first logical segment is everything before は. 死ぬ気になる内容 (The content of the will to die). Although this is long, grammatically it behaves the same way as a single noun. The rest of the sentence is just describing that ‘noun’. (Regrets at your time of death, is what it is).

July 23rd

Translation

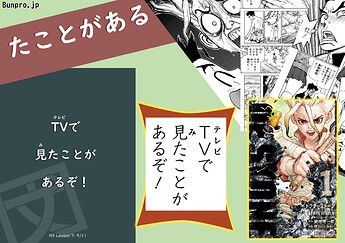

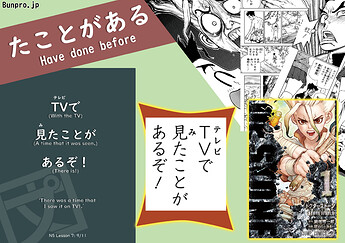

Notes: You may have heard ぞ in several different situations, but something you may not know yet is that it has 2 common uses. The first is when telling someone (of a lower postion) your opinion, or intended course of action, strongly. The second is actually used when one is speaking to themselves, and wants to convince themselves of something that is true. It can almost be thought of as the opposite of っけ. With っけ, this sentence would be ‘Was there a time I saw that on TV?’, but with ぞ, it becomes ‘Oh hey, there was totally a time I was that on TV!’.

July 22nd

Translation

Notes:

付近 is quite a formal way to say 近く in Japanese. It is often heard in announcements and warnings. It is very similar to ‘vicinity’ in English. 方々 (persons) is also a more respectful (not necessarily formal) way of saying 人々 (people). The reason ‘persons’ was chosen here was to illustrate the rare, but still correct language choice, similar to 方々.

July 21st

July 20th

Translation

Notes:

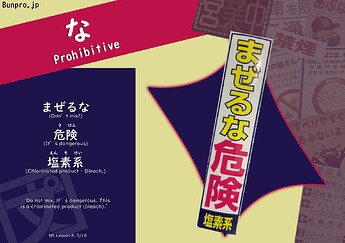

するんじゃね~・すんじゃね~! Because this is an extremely common abbreviation in manga and drama, now is a good opportunity to talk about it! Basically this is a very casual (often angry) expression that means ‘don’t’, or ‘shouldn’t’, do something. If there is a る as the last syllable of a verb, it is often dropped, but not a requirement.

July 19th

Translation

Note: Because Japanese is known as a pronoun free language (avoids using them in most situations), sentences like this can become very tricky. Once you start reading a lot of Japanese content, you will usually have enough context to figure out things like ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘they’, ‘them’ without too much trouble. If it is something that you struggle with now, don’t worry, the struggle won’t last forever!

July 18th

Translation

Notes: Here it is, the double です of doom! (Scientific name). In conversational Japanese, using です twice like this would be considered highly unnatural, and shows that the speaker is A: Not 100% there in the head. B: Being sarcastic (Japan’s version of sarcasm), or C: Possibly an otaku. A running gag in many anime is that otaku use very strange Japanese like ですです, でござる, and of course, finishing sentences with the ニャン (cat sound)

July 17th

Translation

Notes:

One of the most common meanings of 一旦 actually translates best as ‘for now/the time being’. This is an example of that particular usage. Here, while the semi-polite ませんと(same as ないと) may be a bit unfamiliar for some of you, it is actually exceptionally common in manga, particularly when an adult/sensei character is speaking.

July 16th

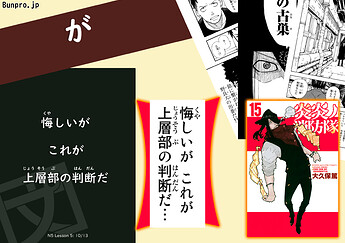

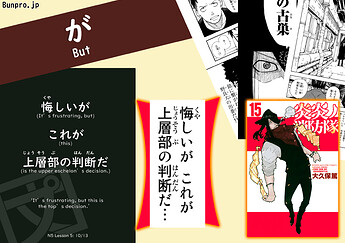

Translation

Note: While 判断 is usually translated simply as decision, it might help to think of it more as ‘the final word’. It has a strong feeling of being the final choice that someone will make, with no compromises afterward. So ‘This is the final word from the top brass’ would also work as a translation!

July 15th

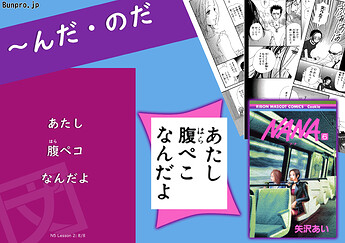

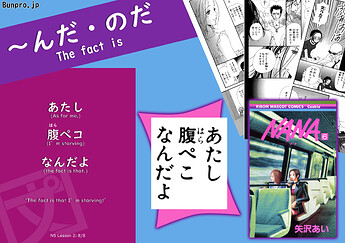

Translation

Notes: This is an example of the explanatory use of ~んだ・のだ, which is also frequently paired with もん or もの when used by women or children. Although we don’t have もん or もの here to give us any indication that the speaker is probably a woman or child, we do have あたし, the feminine form of わたし. Always try to look for clues in sentences as to who might be speaking. There’s almost always hints in their speech style!

July 14th

July 13th

July 12th

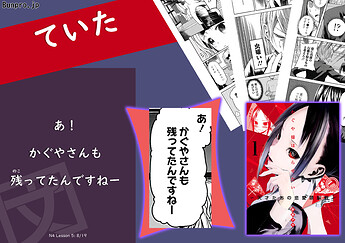

Translation

Notes: While a fair few of you are probably accustomed to the ~てた form of ~ていた that drops the い, something which may also be worth paying attention to is formal speech. A common mistake people make is using the shortened forms in polite sentences. While it might seem like a fairly innocent change to shorten ていた to てた, it actually reduces the formality quite a lot! So you will never usually hear short forms used with any type of keigo.

July 11th

Translation

July 11th Translation

Note: It looks like a few of you noticed the difference between the furigana of one word, and what was being said. This is very common in all types of literature, so requires a strong kanji knowledge at times to realize that the furigana is not actually for the kanji, but actually just a joke or something similar. The furigana portion will always represent the person’s true thoughts, or will just be a dumbed down version of something ridiculously complex the speaker said. When it is ‘dumbed down’, the nuance is usually that the speaker is being pompous, and any normal person would have said an easier word.

July 10th

Translation

July 10th Translation

Notes: The key indicators for what this sentence is trying to convey lay in the ある and the 。。。One of our main notes for かぎり is ‘A限り、B. means that as long as A continues, B will not change’. Here, A is ある and 。。。 is B. The way we can interpret this is that the mere existence of the disk is preventing something, or allowing something. In this case, the character then goes on to destroy the disk, showing that the 。。。 actually meant ‘As long as this disk exists… it’s getting in the way of my plans!’.

What is a MO?

In Japanese: https://e-words.jp/w/MO.html

In English: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magneto-optical_drive

July 9th

Translation

Notes: When trying to figure out what こいつ means, it might be helpful to look at the verb being used (or the speakers emotional state in general). While it is always difficult to figure out the meaning without extra context (like a picture), it could be assumed in a sentence like this that こいつ would probably be a person. Because 復讐 (a very strong word for revenge) is used, it would usually be safe to assume that こいつ would be a person. This would be because the speaker would probably not refer to something that they are strongly emotionally disturbed about as こいつ if it were inanimate. This doesn’t work 100% of the time, but it should help for the majority!

July 8th

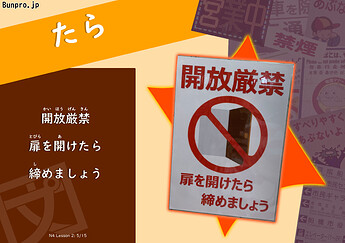

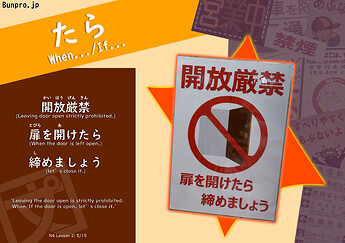

Translation

Here is our translation:

Note: Even though we put ‘close’ here, it might be handy to know that this kanji (締) usually means ‘to fasten’. It has the nuance of ‘closing’ in this instance, but it could also easily be translated as ‘secure’ (so it doesn’t swing open in the wind and smack someone in the face!)

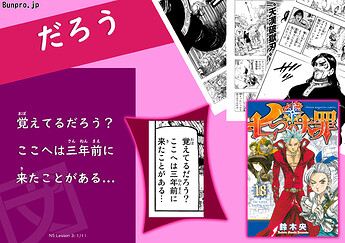

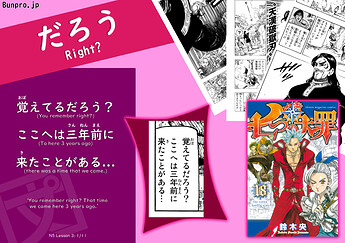

July 7th

Translation

Notes: Who is this about? Is it ‘we’, ‘I’, ‘they’, ‘you’?.. Actually, it is almost certainly ‘we’! For a sentence like this, there are a few giveaway grammar points. 'だろう’, the speaker is looking for agreement about (remembering). If it were ‘me’, then instead of だろう, よ, would probably be used. If it were ‘you’, then ’へは’ would not have been used, as ’へは’ really solidifies the experience of ‘coming’ as the important memory. If only the ‘destination’ was important (implying that they didn’t travel together), then ‘に’ would have been used. What about ‘they’? The は eliminates ‘they’ here, as は refers to something that has a feeling of being complete, or finished/unchanged. We never usually use は apart from the things that we have very intimate knowledge of, so using は here would imply that the speaker knew about all of the actions of the person they were speaking about (very unlikely unless it was themselves).

July 6th

July 5th

Translation

Here is our translation:

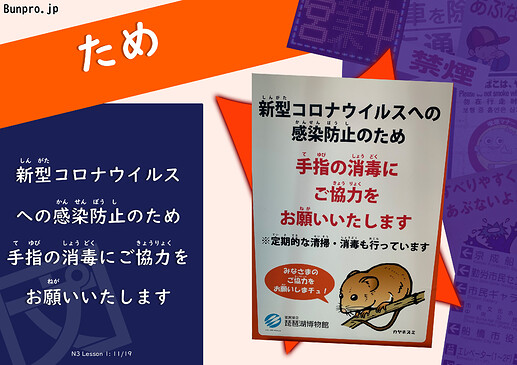

Note: への can be a bit confusing! In this context it would translate as ‘against’ in English. It just separates the location mentally from the action, similar to how へ usually functions. So it’s literally ‘towards corona virus’ as へ would usually behave, but ‘against’ in English.

July 4th

Translation

Something to note: while this may seem like an incomplete sentence, omission of the verb is actually pretty common in conversational Japanese, especially when that verb is いる or ある. This makes it easier for the speaker to make statements that may sound a little mean, or they are just being extremely indirect. If you see a sentence finish on が, you can usually guess the missing verb from context. 90% of the time it is either いる or ある.

)

)