It took me five times to get it right. I felt it was a challenge.

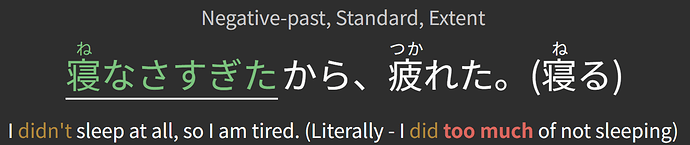

In my first attempt, I conjugated 過ぎるin the negative, not 寝る. There was a literal translation to help, but I paid it no mind. I had been doing many “Must do” reviews with a doble negative. From that, I learned that, in most cases, the negative belongs to the main meaning, not to 過ぎる.

In my second attempt, I conjugated the negative of 寝るas ねらない, as I thought that 寝る was a godan verb, like most of what I call “short verbs” -composed only by a kanji and る-. From that, I learned that 寝るis an ichidan verb, and I added it to my mental list of “short vebs that are NOT godan” -until now (I’m in WK level 18), 見る, 着るand 寝る-.

In my third attempt, I wrote ねさな, instead of ねなさ, because that the negative has a さwas all I could remember. I realized then that I didn’t know what this strangeさwas, and what was doing there. I went back to Bunpro Grammar. さis equivalent to く, a conjugated form of ない. It had been explained before, but for me, it was then and there, when I fully understood that ないthe negative form of a verb is an い-adjective. There it was, behaving like an い-adjective in all its glory. It was one of those Woah! moments.

In my fourth attempt, I didn’t write 過ぎる in past tense. Just in case, I checked it in jisho. It looked like an ichidan verb, but that ぎwas so uncommon. From that, I learned that a -ぎるending could be ichidan.

When I wrote it right in my fifth attempt, it felt so good. For me, it was not demoralizing, maybe because each attempt helped me to learn or reinforce something. I was learning, it didn’t matter that it was in a single review that had got stuck.

Sorry for the long digression. I have written it, just in case this way of viewing can help someone.

Of course, with an agglutinated word -with various components- it’s more difficult to get it right at the first attempt. But that’s what Japanese is.

In my case, it may have helped that -I don’t know how to express it- I feel “at ease” with an agglutinative language. I am from the Basque Country, in Spain, and I speak the Basque language, which is an agglutinative language. To conjugate verbs, I add various particles to give different types of information. There is no specific sentence order, but the verb always goes at the end. The dictionary form of the nouns is just the stem form, and they always need a particle to be added to mark the case. Words are built by adding words or particles -we have particles that correspond exactly to concepts like, for example ∼ 者∼家∼的∼肉. There are onomatopoeias – although not as many as in Japanese-, words repeated (々)… It is also an ergative language, which have helped me understand the ergative behavior of some intransitive verbs in Japanese.

Maybe that is why, at times, I feel so “at home” with the Japanese language. But that makes learning Japanese grammar, explained from the English grammar perspective, at times, also a bit frustrating. I try to identify -I’m getting better at it- when an explanation is of no use to me, or worse, when it makes even more difficult for me to understand the item.

What’s the big deal with the sentence order? What’s the problem with the verb at the end of the sentence?

Sorry for forgetting. Of course, verb at the end of the sentence is a problem. It’s not a question or reading “backwards” -there was a post about it-, which it’s impossible. I think it’s a question of training the mind. For reading, you must create something like “temporary files” at the front of your mind, where you file tidily the different information as you read the sentence, to bring back right away when you reach the verb. For producing, you must have decided beforehand all you want to say, file this information tidily in this “temporary files” and then take them out, one by one, in the order you want, leaving the verb to the end.

Basque language is not my mother tongue, I learned it later -so did many of the Basque people, it was a language at high risk, now it’s recovering-, and I remember that I had to train my mind that way to be able to read and speak it fluently.

I decided to learn Japanese on a whim, nine months ago. Back then, I didn’t know anything about the language, or its writing systems or anything, I think that the only words I knew were さようなら, かたなand かわいい.

I started without expectations. So, what I found was completely unexpected. Surprise after surprise, so many woah! moments. And always this contradicted feeling of familiarity and strangeness at the same time. So many times, had I found myself thinking “How is it possible for a language to be built like that?”

Probably, the most mentally challenging activity I’ve engaged in years, frustrating sometimes, but always rewarding. A joy.

I’d like to share some of my experiences on this journey. I’d like to know if some of you have experienced some of my “firsts” too.

And laugh with me. Just so you know, but, before I started learning Japanese, although I knew that kanjis exist, I thought that they were a cultural stuff, from de past, I wasn’t aware that they really used them, that they are an integral part of the Japanese language.

Another time.