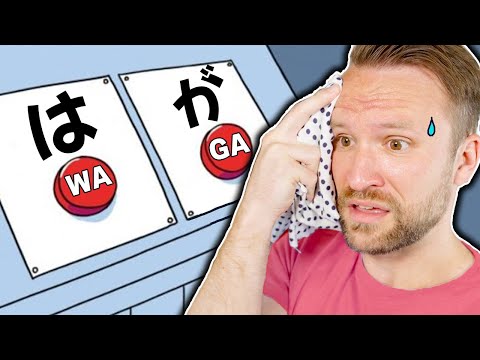

Often when comparing these, their differences become clear, but what I often find is left out, is when you just want to say a plain sentence?

For example, using https://www.wasabi-jpn.com/japanese-grammar/ha-vs-ga-five-points-you-need-to-know/

My biggest confusion with the が vs は is that it is almost always discussed as having two separate meanings that don’t actually cover a very wide range. They are both described in ways that leave me utterly confused how to make a bland/plain statement without the two nuances.

In the article it says “If someone asks you, “Do you like fruits?” and then you say, 「オレンジは好すき」, this indicates that you like oranges, but don’t like other fruits very much; that is to say, you generally don’t like fruits. If you say, 「オレンジが好すき」, this just indicates that you like oranges more than other fruits.”

So what if I simply want to say I like oranges, I do not want to contrast it with others saying I like it more than those, nor do I want to say I don’t like any other fruit. It’s just a bland statement of “I like oranges”? And yes in that example it’s being prompted by a question then you are specifying one singular type of fruit so it’s already a bit different, but my question below remains the same.

If I want to say “I like horses” which particle is the one to use? I do not want either nuance, not to contrast, nor to identify and rule out other options.

So I know people will not be happy with this next part but I hope you can not take it as me saying these are authoritative resources but see I’m using it to describe the confusion that goes on here.

So I went ahead and asked both the Hiinative bot and Chatgpt a very simply question. The question above, how would I state a plain sentence of “I like horses” without wanting to have contrast or say I like it more than other animals, a plain equivalent to an English "I like horses.

ChatGPT: 馬が好きです (Uma ga suki desu) - I like horses. This is a neutral statement expressing your liking for horses without specifying that you dislike other animals or that horses are your favorite. In this context, が is used to identify the subject of your liking.

ai_monga (Hiinative) : When we say ‘馬が好きです’ (uma ga suki desu), the particle ‘が’ (ga) is used to mark the subject of the sentence. This sentence structure puts emphasis on the subject, implying that you specifically like horses, as opposed to other animals or things. It suggests that horses hold a special place in your preferences or interests.

Example: 馬が好きです。(Uma ga suki desu) - I like horses.

On the other hand, when we say ‘馬は好きです’ (uma wa suki desu), the particle ‘は’ (wa) is used to mark the topic of the sentence. This sentence structure puts emphasis on the topic, which is horses in this case, but it doesn’t necessarily imply exclusivity. It suggests that you have a general liking for horses, without comparing them to other animals or things.

As you can see they answered entirely flipped from one another, and they are trained off of publicly available info, which is my point, even the AI does not reach a clear conclusion from the publicly available info, they end up contradicting each other, which I think really points to the difficulty of this discussion.

I hope you can see what I am saying here, and please feel free to give me any guidance, along with answer my innate question of how to make a plain statement without either of the two nuances. Just a plain “I like horses”